Published in 1909 at the height of Britain’s imperial reach, The British Empire (and Japan) atlas is a carefully conceived thematic atlas compiled under the direction of W. Bisiker that reflects both the geopolitical realities and the educational aspirations of the Edwardian era.

As the title and preface make clear, the atlas is primarily devoted to the British Empire, conceived explicitly as a tool for “Education and Empire.” Its creation coincided with intense public and institutional debate in Britain about imperial education, especially following the Colonial Conference of 1907. Bisiker’s response was to design a work that would make the Empire intelligible as a living, interconnected system of territory, resources, peoples, and trade.

Japan’s inclusion—unusual in a British imperial atlas—is explained by contemporary politics. As Britain’s ally following the Anglo-Japanese Alliance of 1902, Japan is presented alongside the Empire as a partner of strategic importance. The two concluding pages devoted to Japan underline its perceived parity as a modern, industrial, and imperial power, while also reinforcing Britain’s global outlook beyond its formal possessions.

Bisiker explicitly rejects the “conventional lines of the atlases that have been in vogue for the last two or three generations.” Instead, this atlas is organised thematically and pedagogically. Many minor place-names are deliberately omitted so that the maps themselves remain legible and expressive, with emphasis placed on relationships—between relief and transport, climate and production, population and industry.

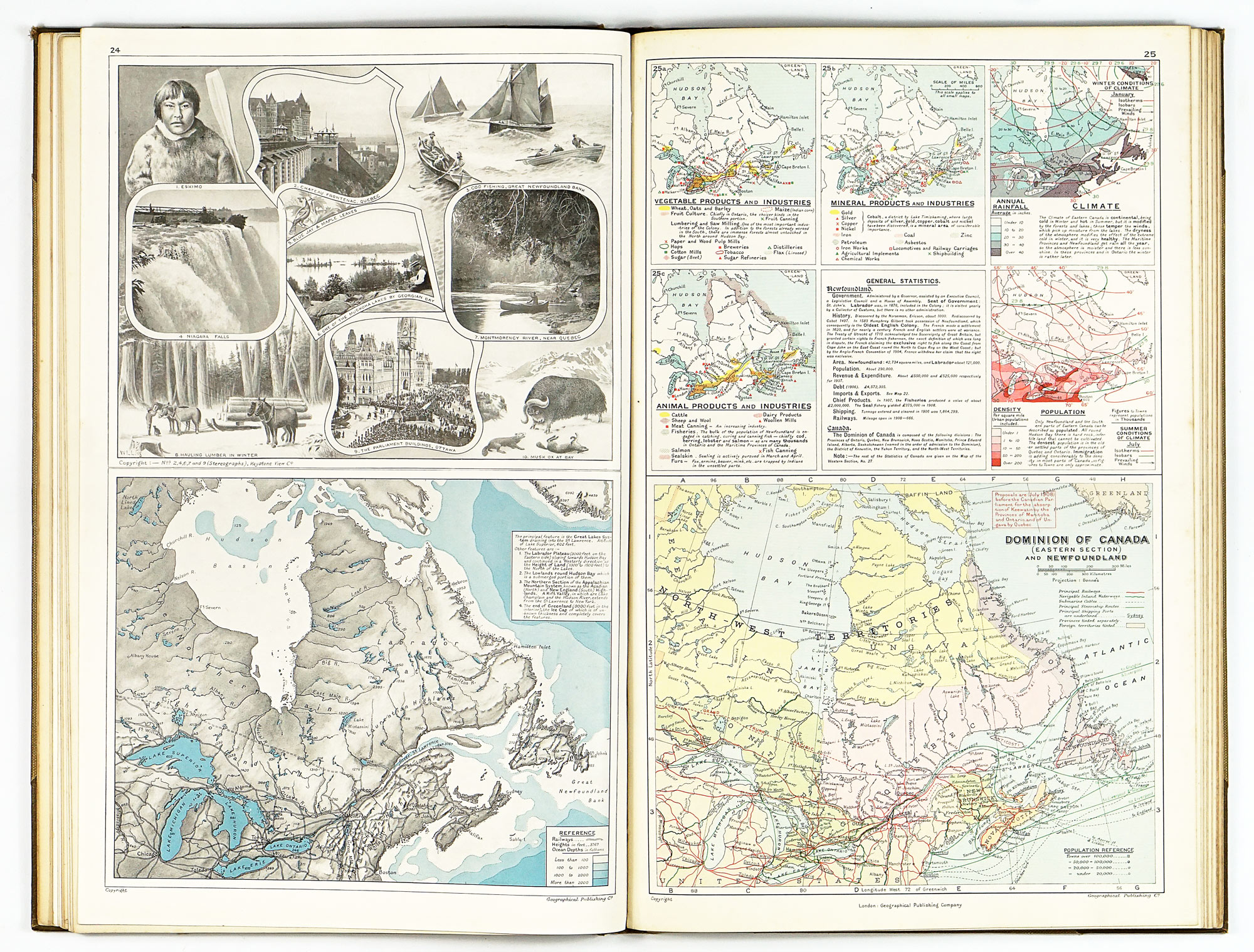

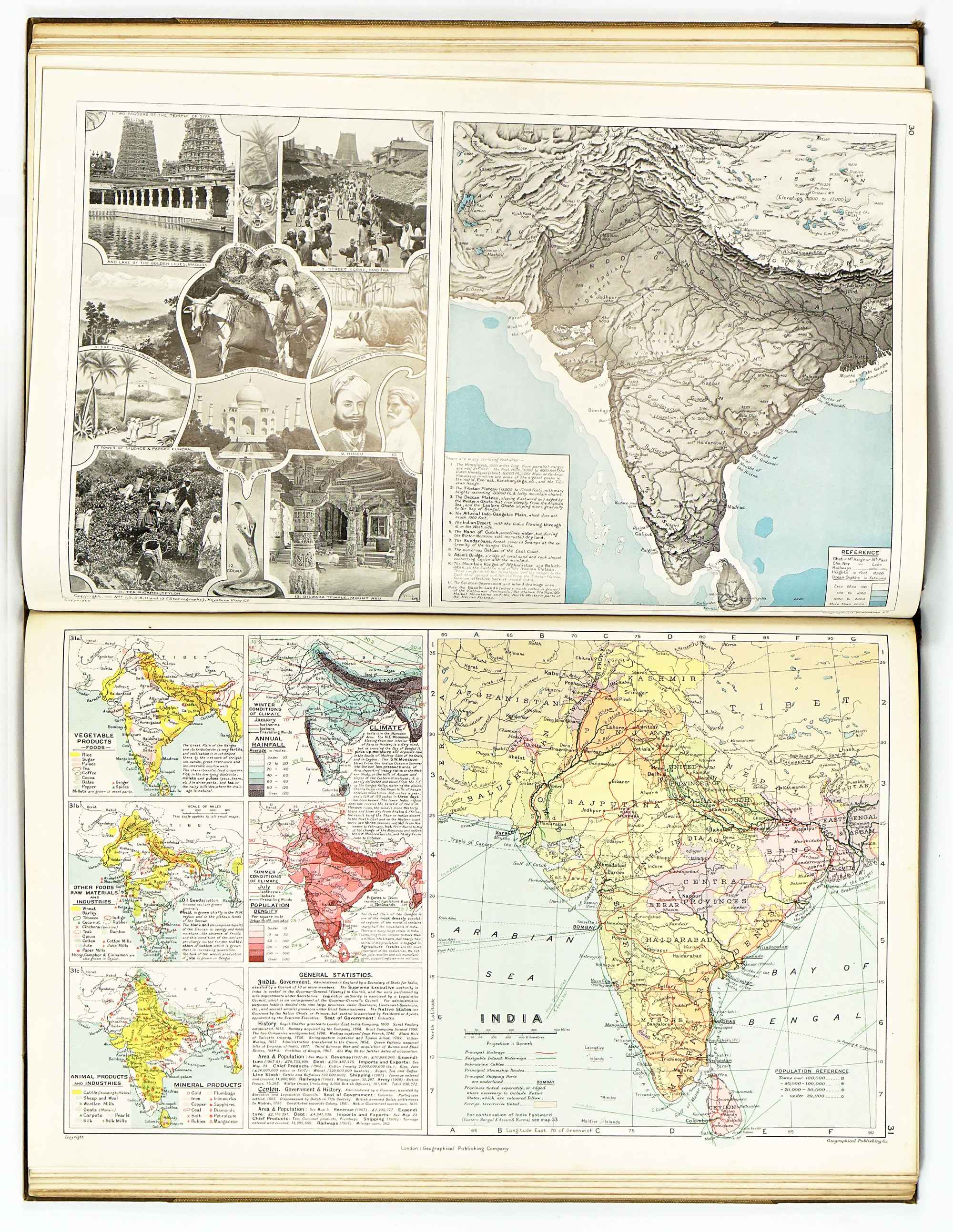

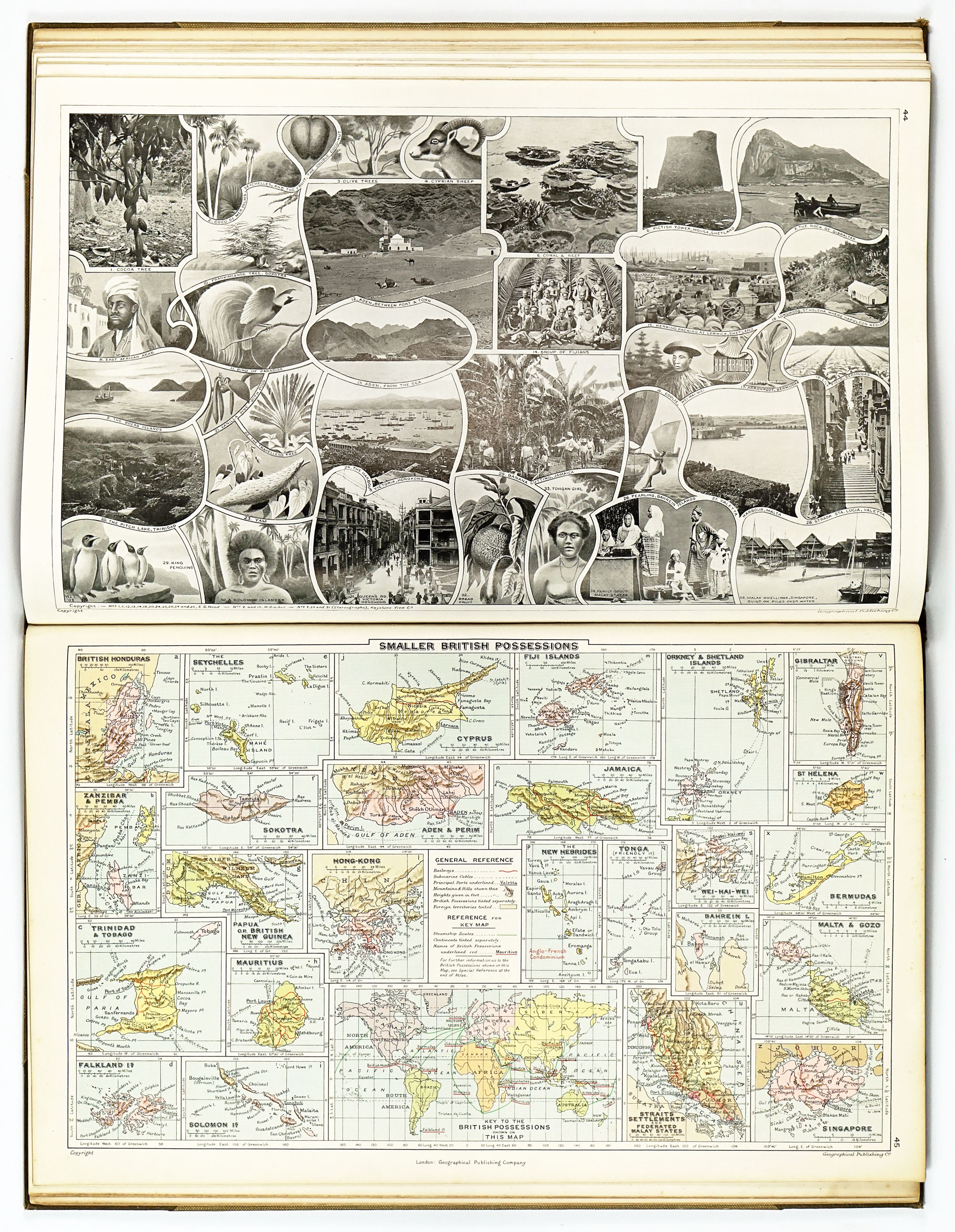

The central innovation lies in the regional plates of the British Empire. Each region is treated as a comprehensive visual and textual unit, designed to be studied “at an opening.” A typical plate combines:

- A large political map showing administrative boundaries, railways, inland navigation, submarine cables, steamship routes, and ports

- A corresponding physical or relief map with shaded relief, carefully drawn to reflect accepted configurations of landforms and ocean depths

- Several smaller thematic maps illustrating climate, population density, and the distribution of vegetable, animal, and mineral products or industries

- A set of photographic and drawn illustrations depicting scenery, inhabitants, flora, and fauna

- Accompanying explanatory text summarising physical geography, government, brief history, and key statistics relating to finance, trade, transport, and defence

This integrated approach is exemplified by the plates devoted to India, Australia, and other major imperial regions, each functioning as a concise geographic “portrait” rather than a mere cartographic inventory.

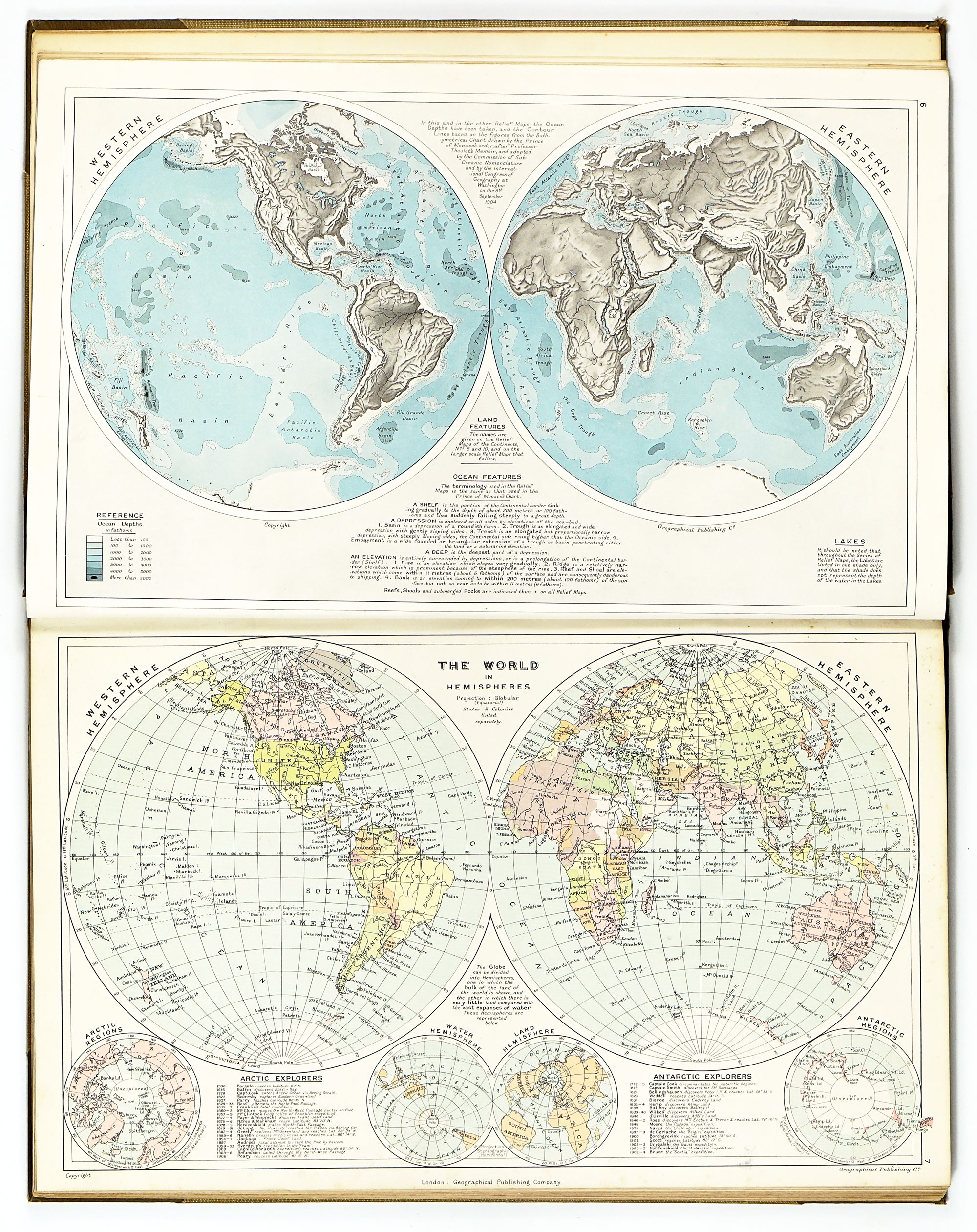

One of the atlas’s notable features is its extensive use of relief maps. Seventeen such maps are included, all with ocean depths rendered in graduated blue shading—still a relatively novel and technically demanding approach in 1909. Railways are overlaid on the relief to demonstrate their relationship to terrain, reinforcing the atlas’s emphasis on geography as a determinant of economic and political development.

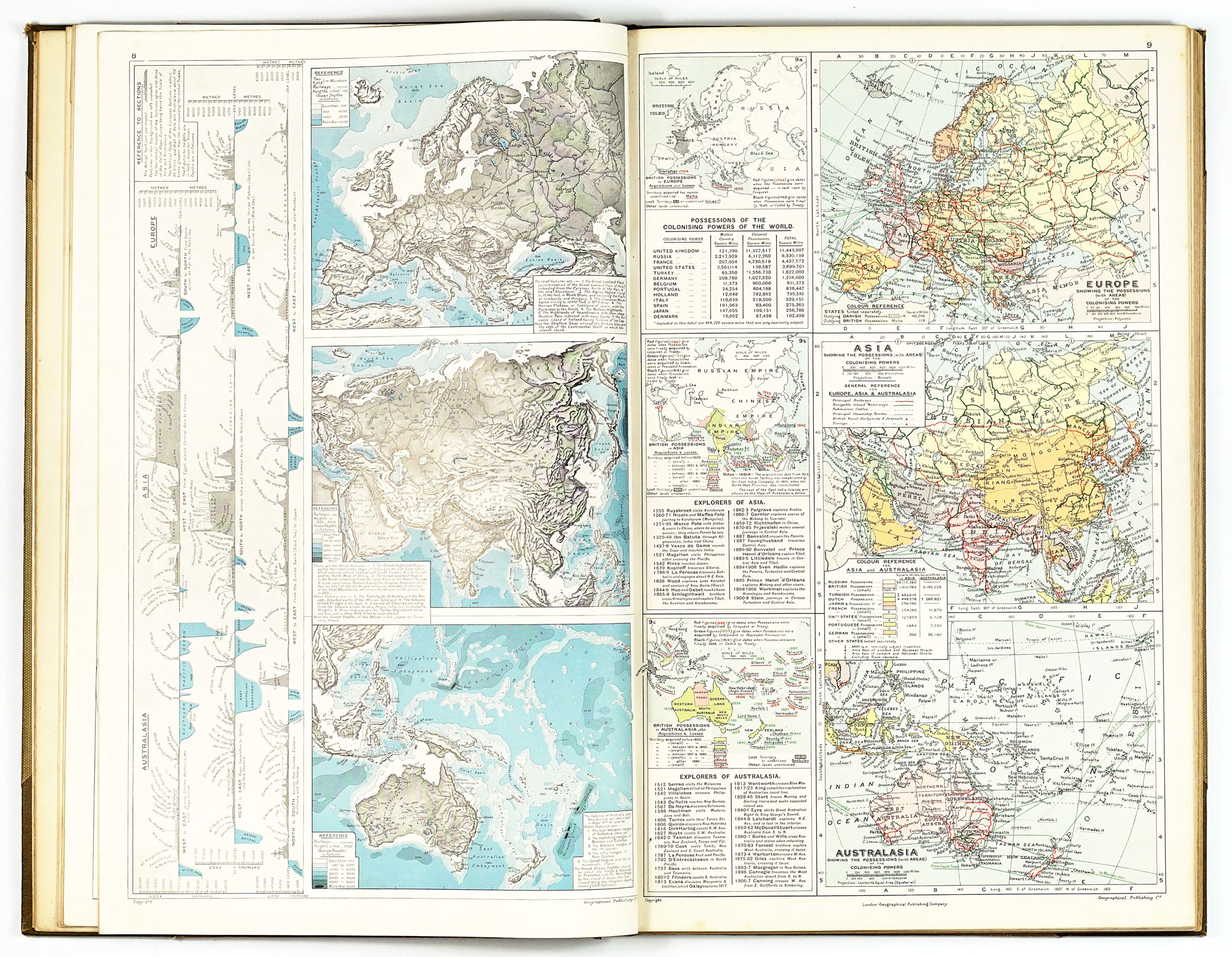

Continental maps are supplemented by transverse altitude sections running from ocean to ocean, vividly illustrating variations in elevation and reinforcing physical geography as a foundation for understanding climate, settlement, and production. These maps also incorporate lists of dated events relating to geographical exploration, alongside small historical inset maps documenting territorial acquisitions and losses. Brief accounts of major explorers’ work further situate imperial geography within a narrative of discovery and expansion, a perspective characteristic of early twentieth-century British cartography.

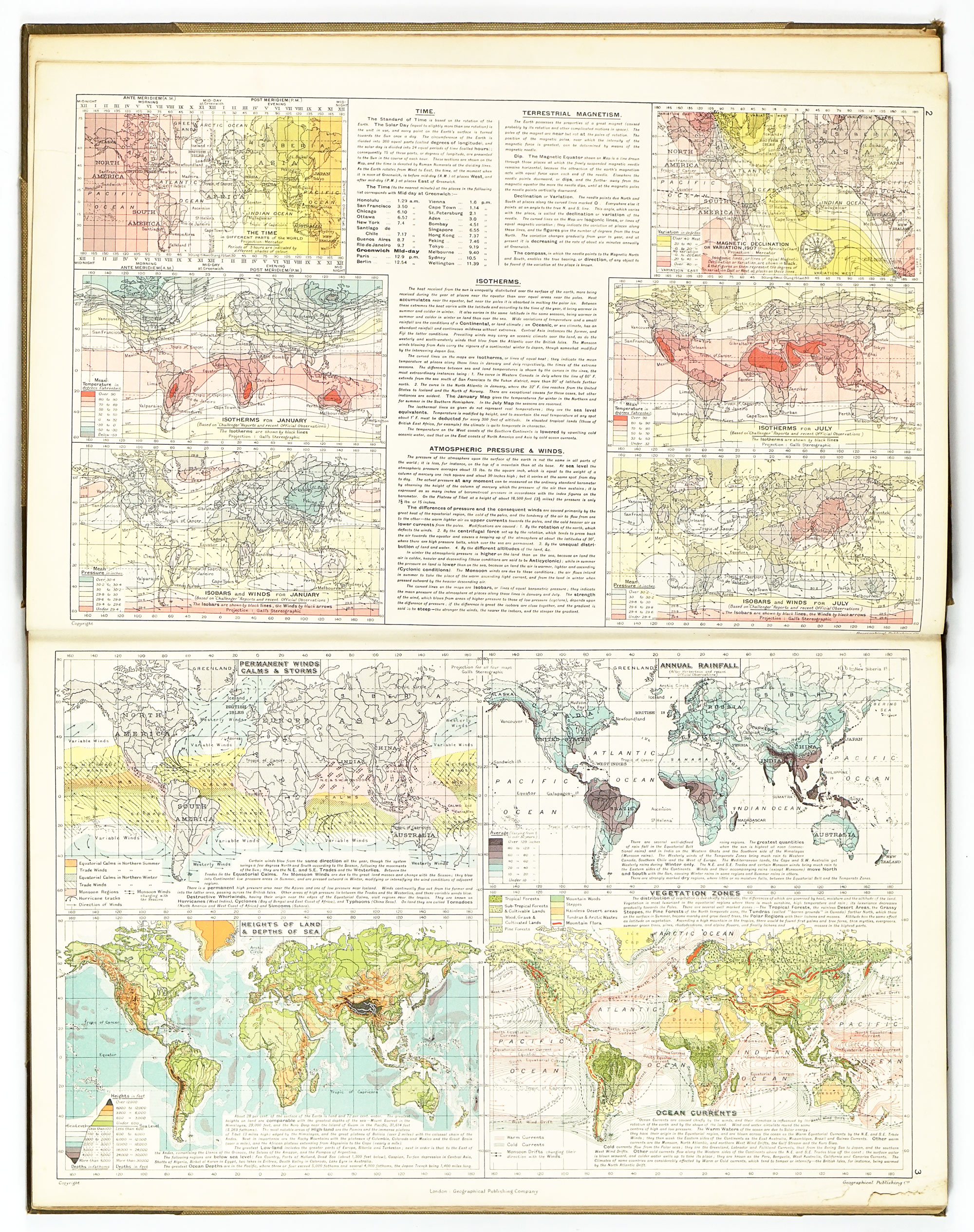

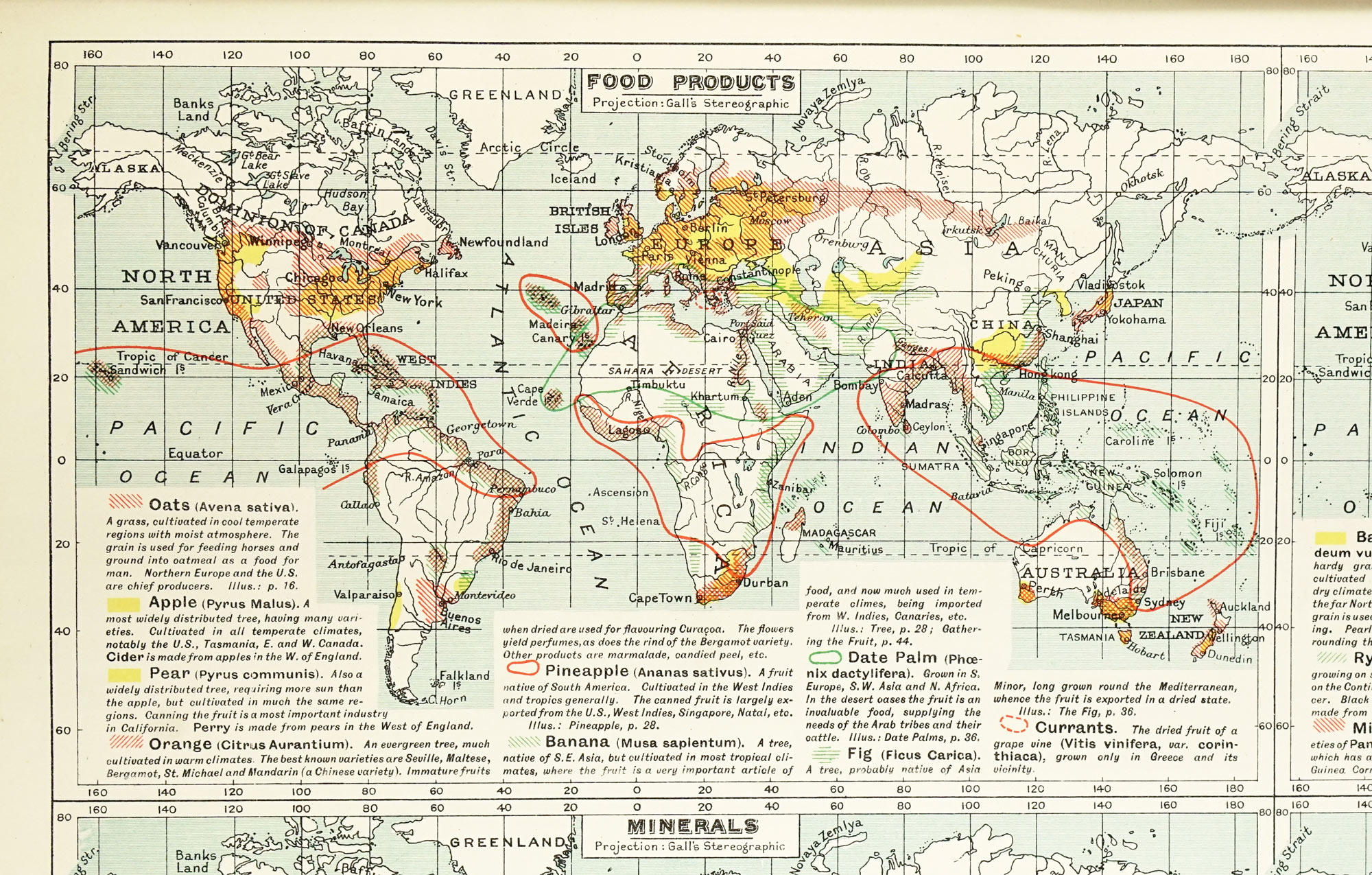

Beyond imperial territories, the atlas devotes considerable space to global physical conditions. Sixteen world maps address subjects such as atmospheric pressure, winds, rainfall, ocean currents, magnetism, tides, volcanoes, earthquakes, and vegetation zones. Each is accompanied by concise explanatory text, intended to make the atlas largely self-sufficient without constant reference to other works.

True to its imperial purpose, the atlas places exceptional emphasis on commerce and production. A dedicated series of twelve maps illustrates the global distribution of over seventy economic products, including foods, raw materials, and minerals, each identified and described directly on the maps. Additional products are catalogued in detailed lists at the end of the volume. In this regard, the atlas is similar to the Atlas of the World's Commerce, published in 1900 by J. G. Bartholomew.

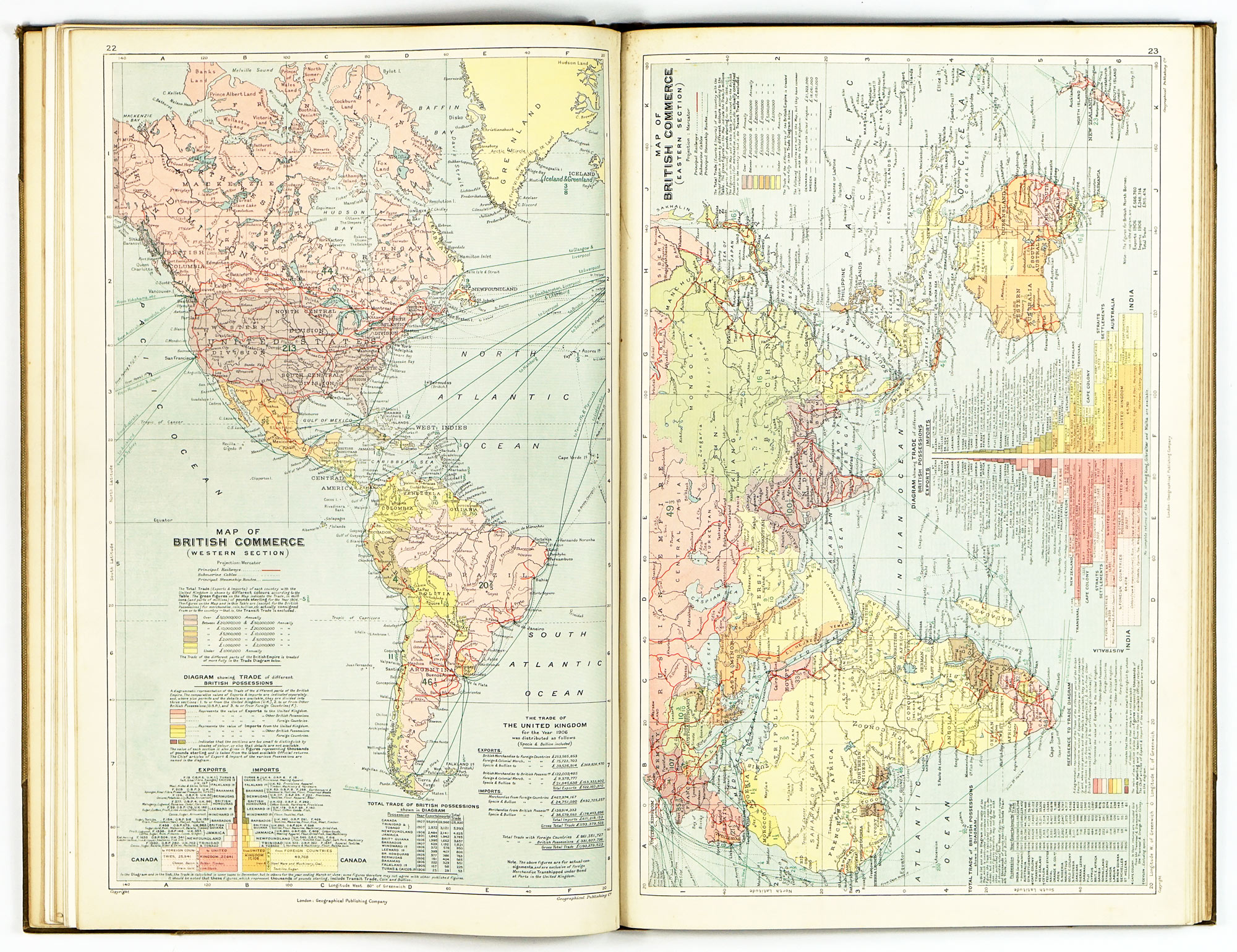

Two commerce maps visualise the trade relationships between Britain and its colonies or foreign partners, supplemented by diagrams showing the relative proportions of exports and imports with the United Kingdom, other British possessions, and foreign countries. Notably, the atlas uses trade figures from 1906 rather than the inflated “boom year” of 1907, reflecting a conscious effort at statistical sobriety.

In addition to maps, the atlas is rich in statistical data: areas and populations of colonies, protectorates, and spheres of influence; general statistics for smaller and less frequently mapped British possessions; and lists of principal commercial products.

The British Empire (and Japan) is a didactic work that integrates cartography, statistics, illustration, and explanatory text into a unified educational instrument. Its emphasis on relief, thematic mapping, and visual synthesis anticipates later developments in twentieth-century atlas design, while its content provides a revealing snapshot of imperial ideology at its zenith.