Following the mathematically and scientifically grounded Erste Abtheilung, the second, third, and fourth parts of Heck’s Bilder-Atlas—presented here in its first edition—mark a decisive shift from the laws of nature to the spatial, historical, and cultural dimensions of humanity. Together, these three sections form the humanistic core of the atlas project, visualizing how 19th-century scholarship understood the Earth as inhabited, shaped, and divided by peoples, states, cities, and historical processes.

While conceived as distinct sections, Geography, History, and Ethnology are intellectually interdependent. Their plates reflect a world view in which physical space, historical development, and human diversity are inseparable—an approach characteristic of encyclopedic thought in the mid-19th century.

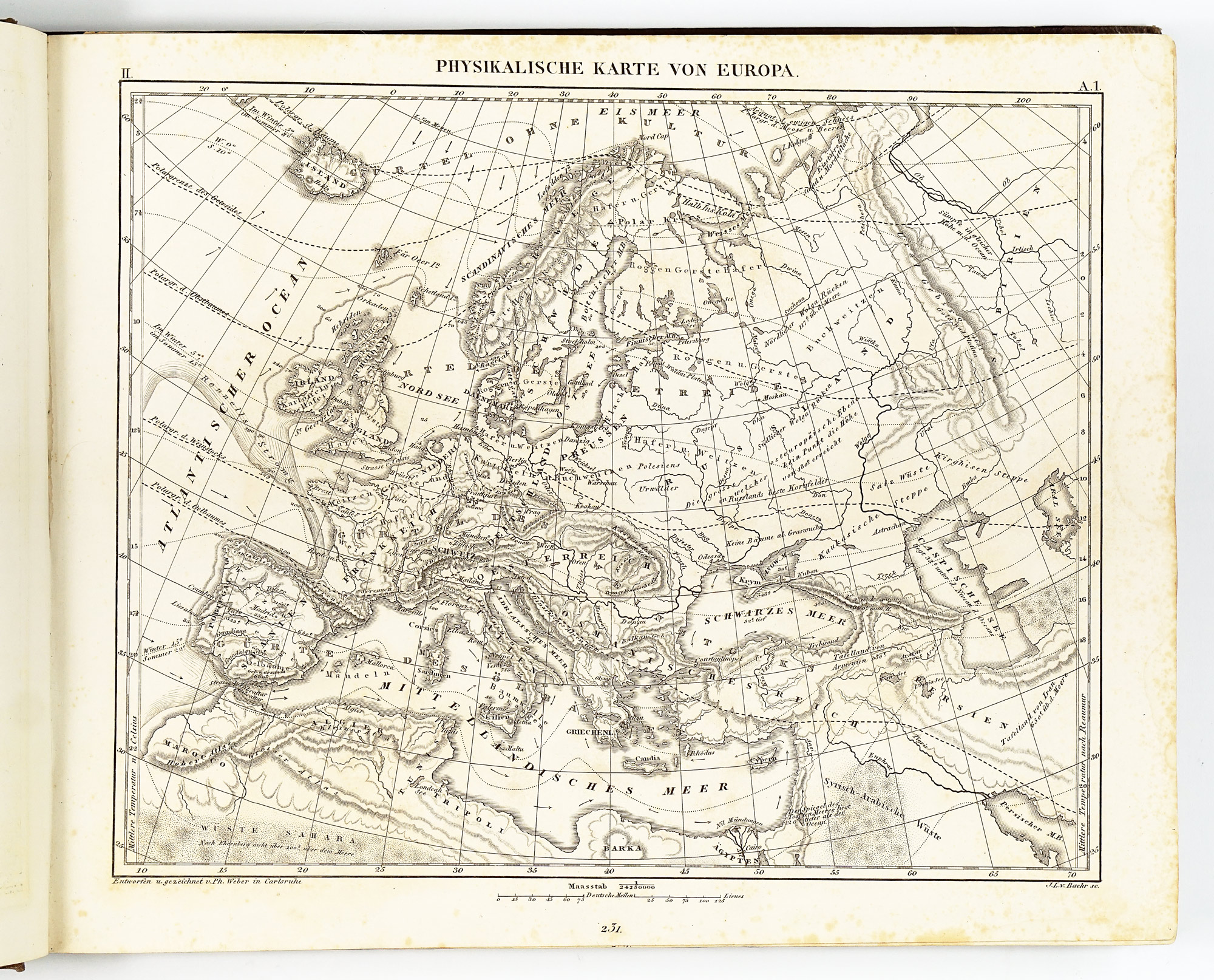

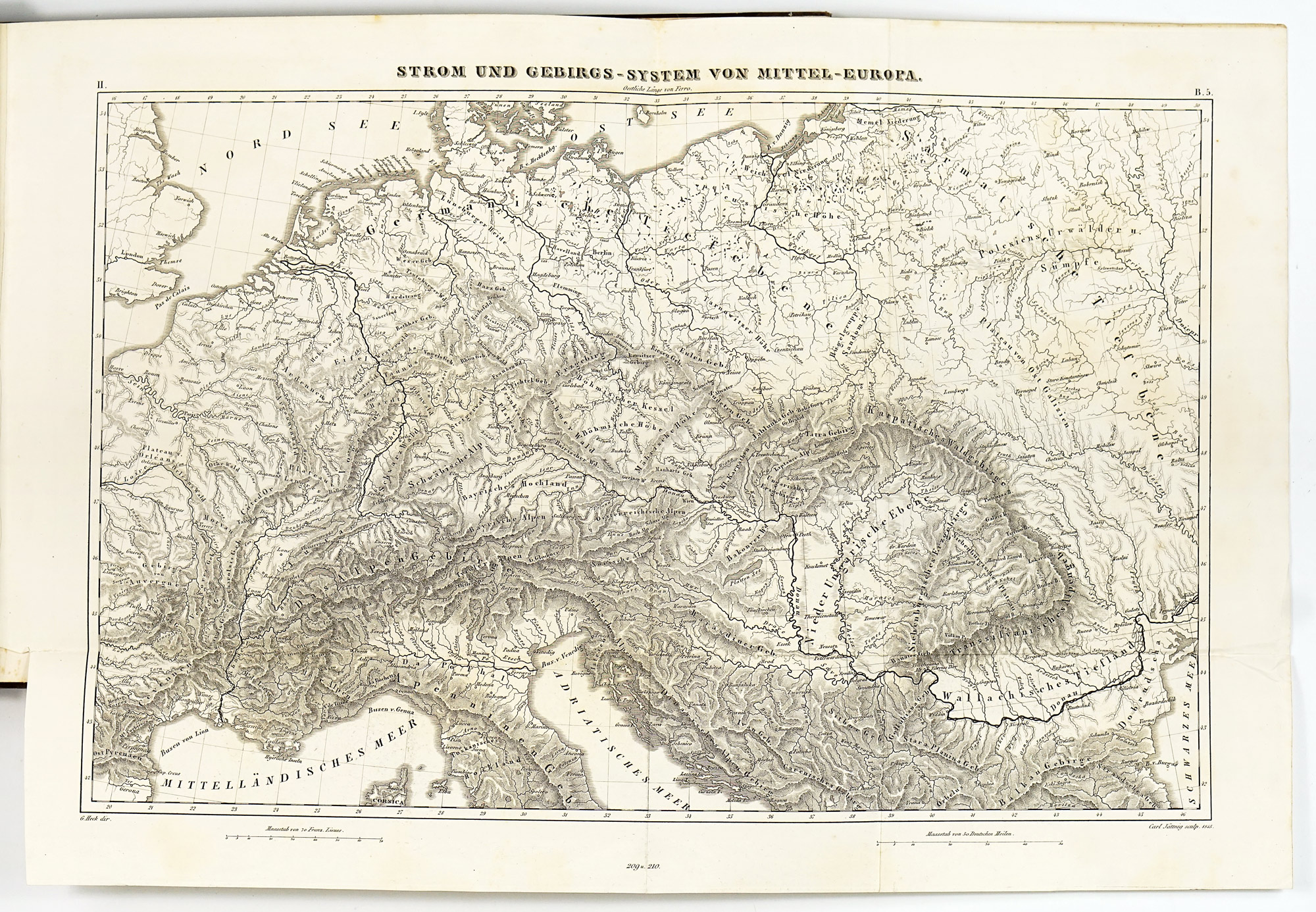

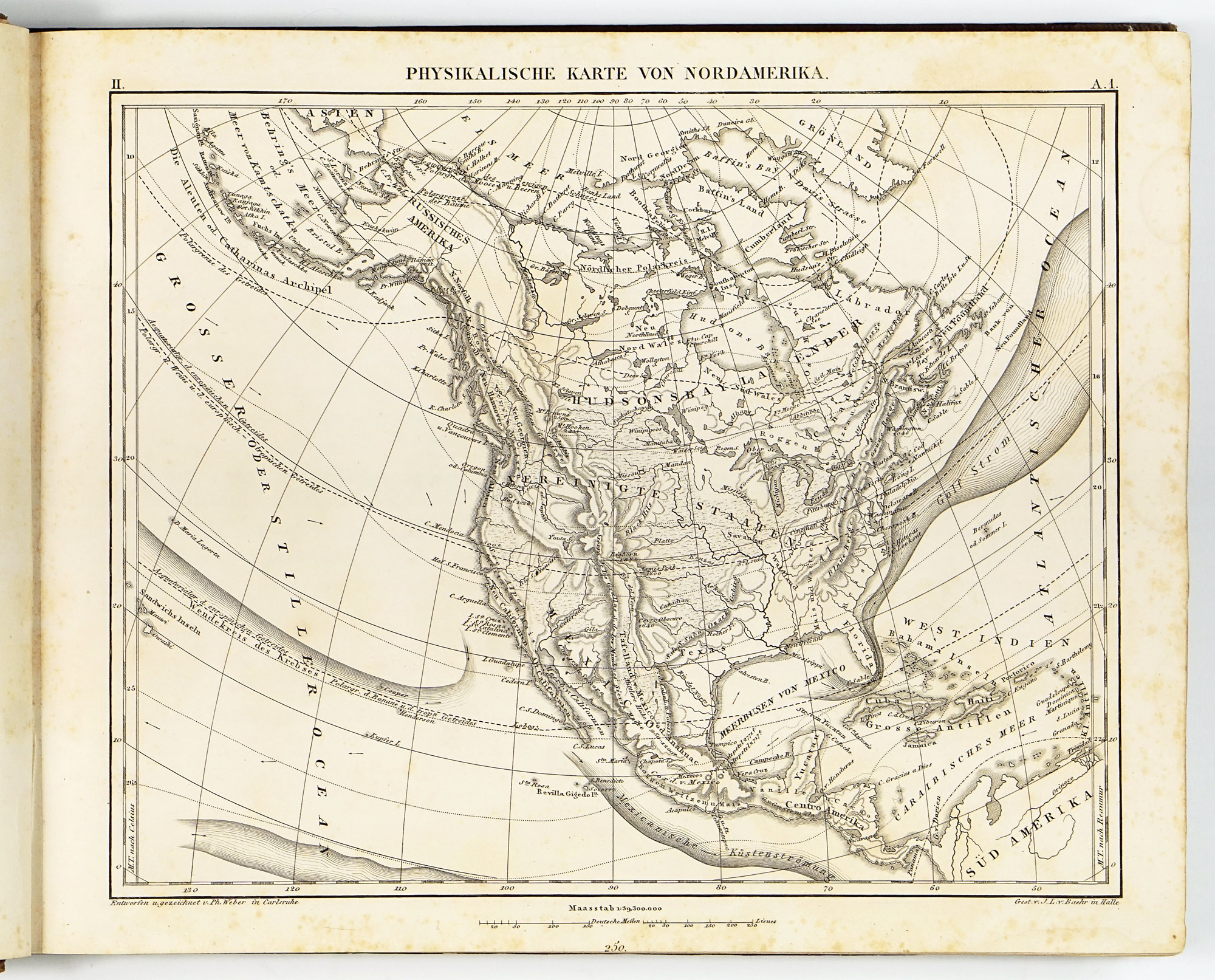

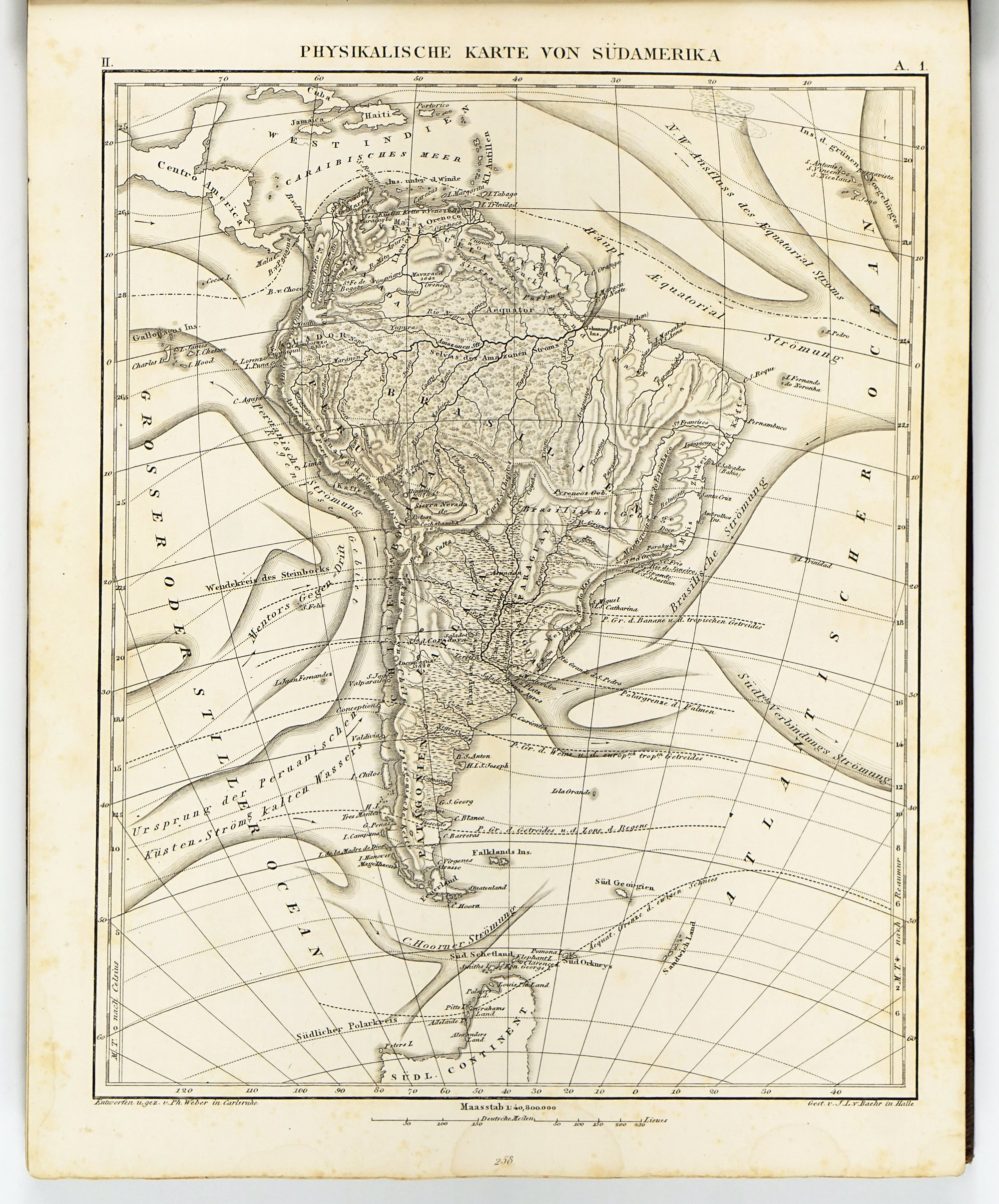

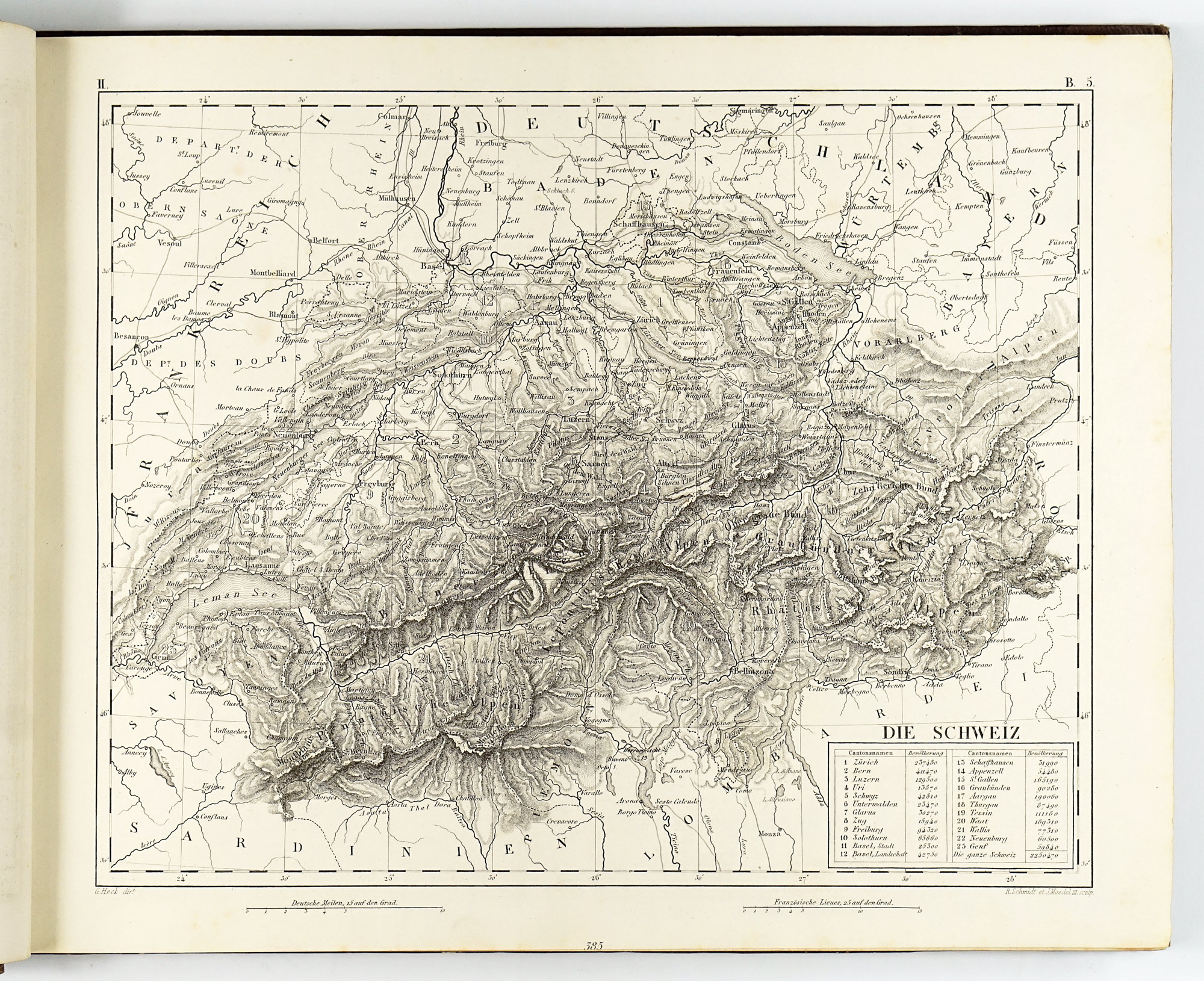

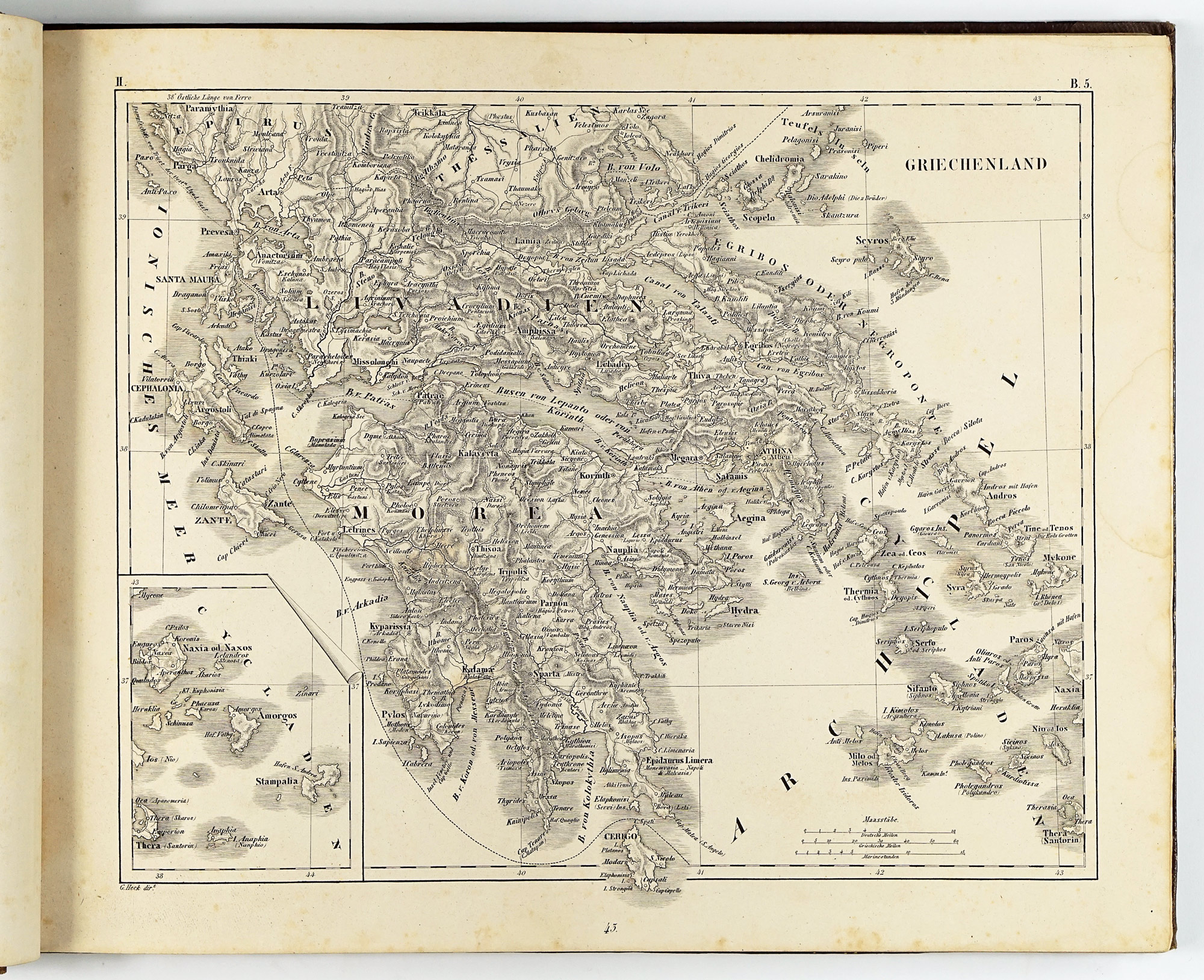

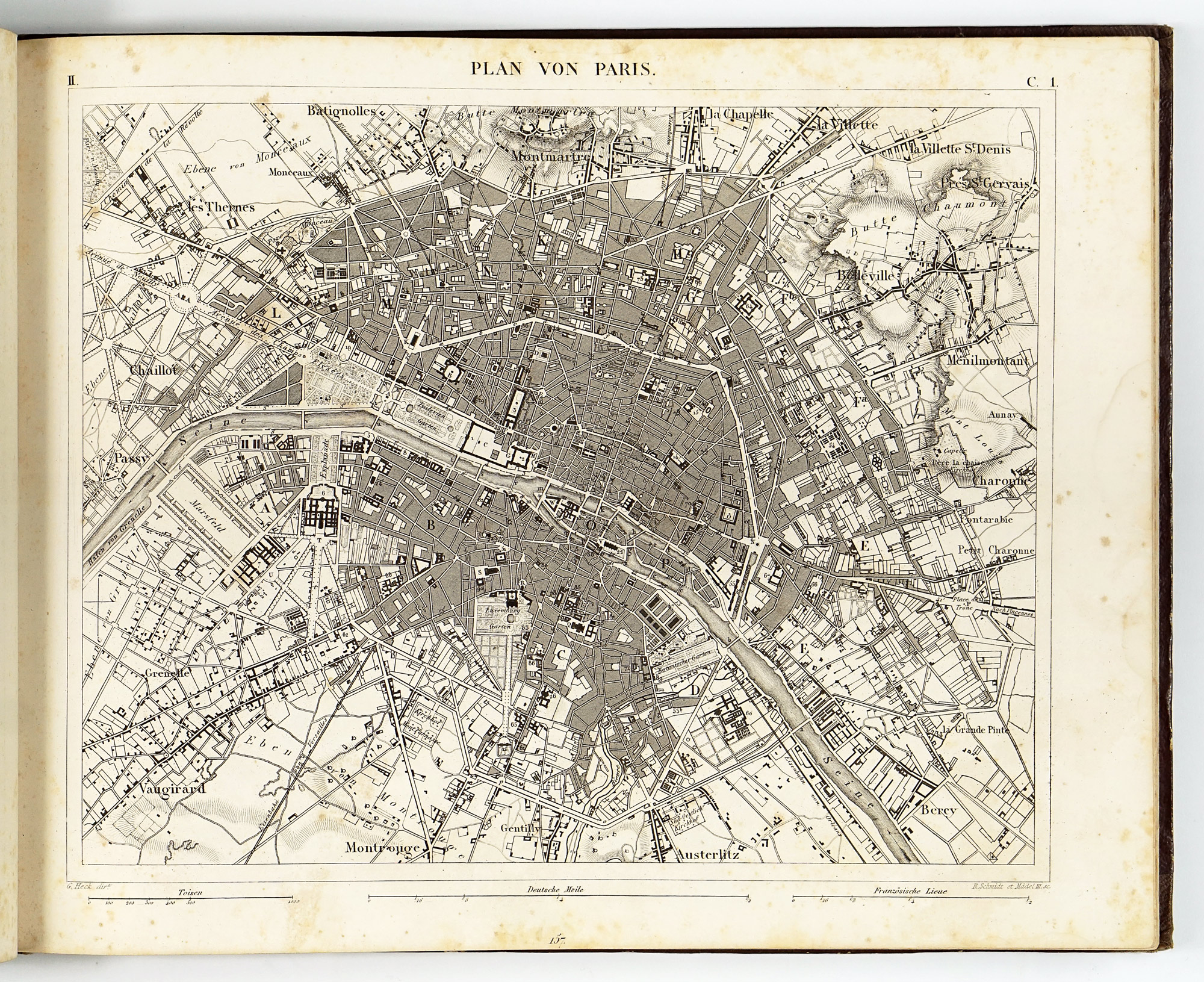

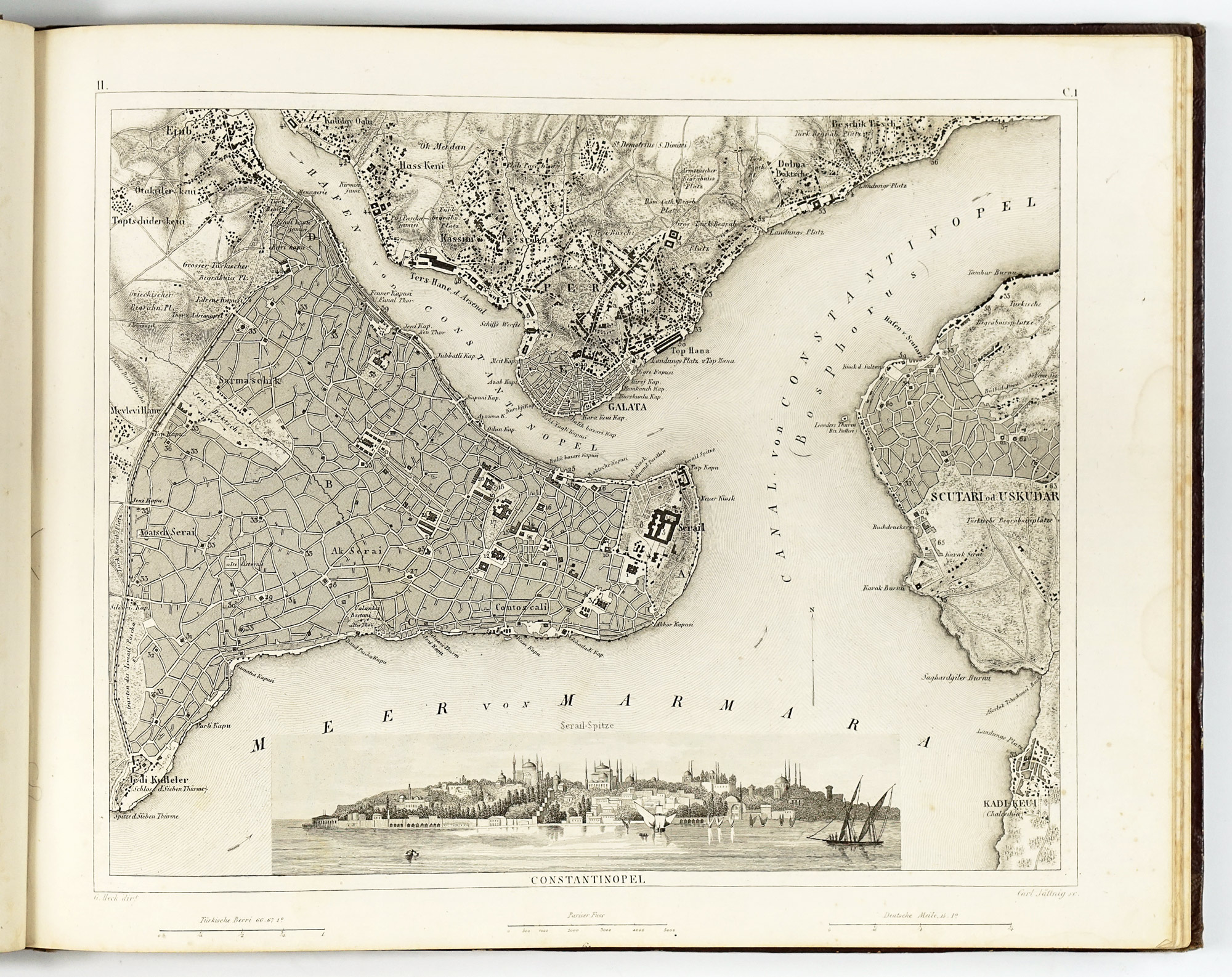

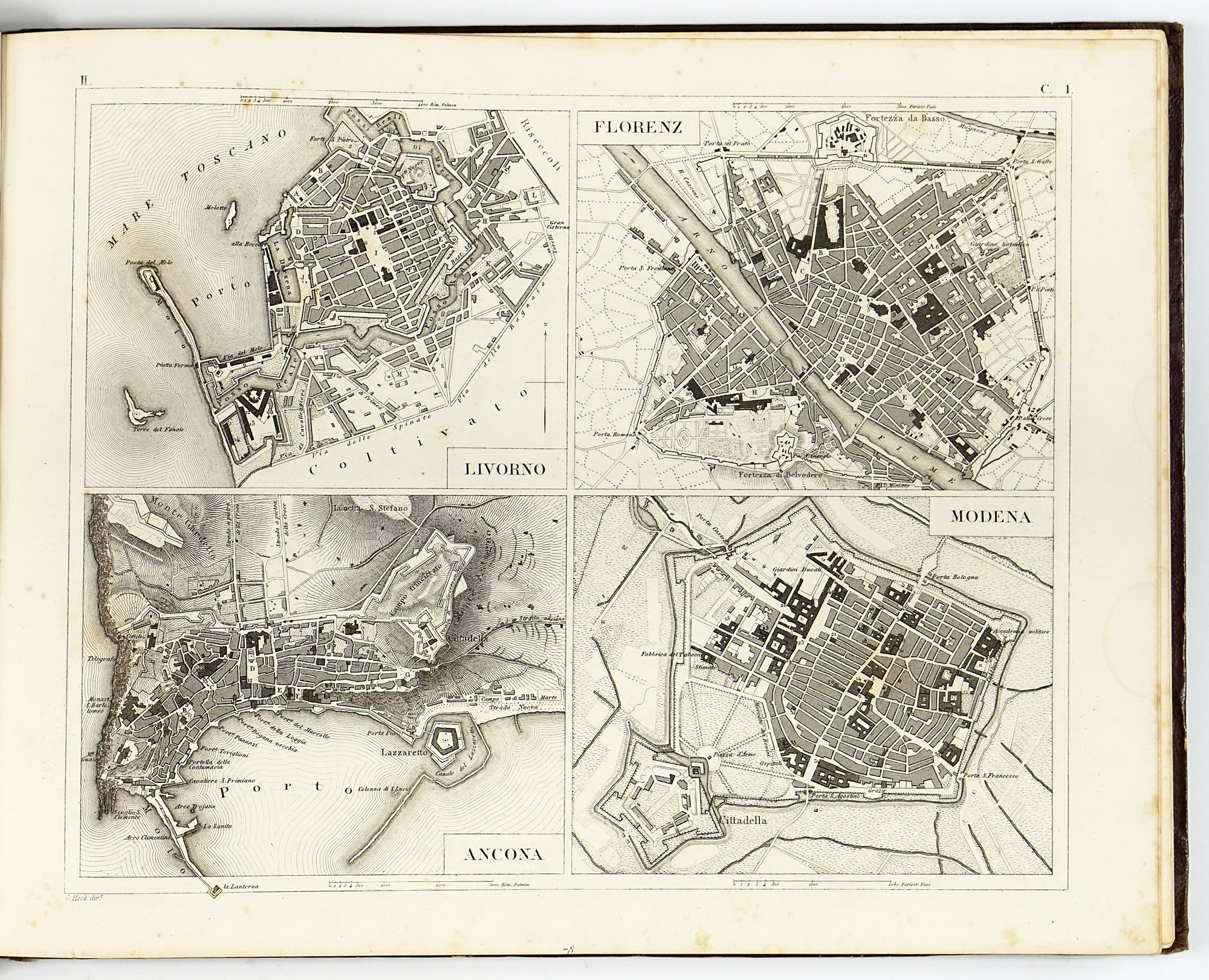

Part II: Geography — 44 plates

The geographical section is the most traditionally “atlas-like” part of the Bilder-Atlas. Although the maps were issued uncoloured, they are finely engraved, richly detailed, and remarkably easy to read. At first glance, the physical maps may appear somewhat dull compared to traditional atlases, however when closely inspected, a wide range of carefully encoded information is revealed, including, ocean currents, continental shelves with depth soundings, the distribution and boundaries of major organic products and animal species, ethnic groups as well as isotherms indicating mean annual temperatures.

The historical maps present a series of distinct historical worldviews, ranging from classical conceptions (Ptolemaic, Herodotean, and Strabonian) to later historical world maps. They address subjects such as the empire of Alexander the Great, the Roman Empire, the Crusades (Kreuzzüge), and the political landscape of Europe before the French Revolution of 1789.

The political maps go beyond administrative divisions and subdivisions of states to document contemporary technological change. Of particular interest may be the detailed treatment of the rapidly expanding railway network, including a fold-out map devoted specifically to the railway system of Central Europe. The map of the United States is accompanied by a contemporary list of thirty states (including Texas) and five “districts” (territories), providing valuable historical context.

Particularly notable is the large number of urban plans included, depicting 21 cities—among them London, Paris, Istanbul, St. Petersburg, Vienna, Rome, Milan, Madrid, Lisbon, Amsterdam, Copenhagen, Stockholm and several others—spread across 12 plates. In these plans, major buildings are highlighted, marked by a number and explained in the accompanying encyclopedia text, giving the Bilder-Atlas clear and practical advantage over more conventional atlases of the period.

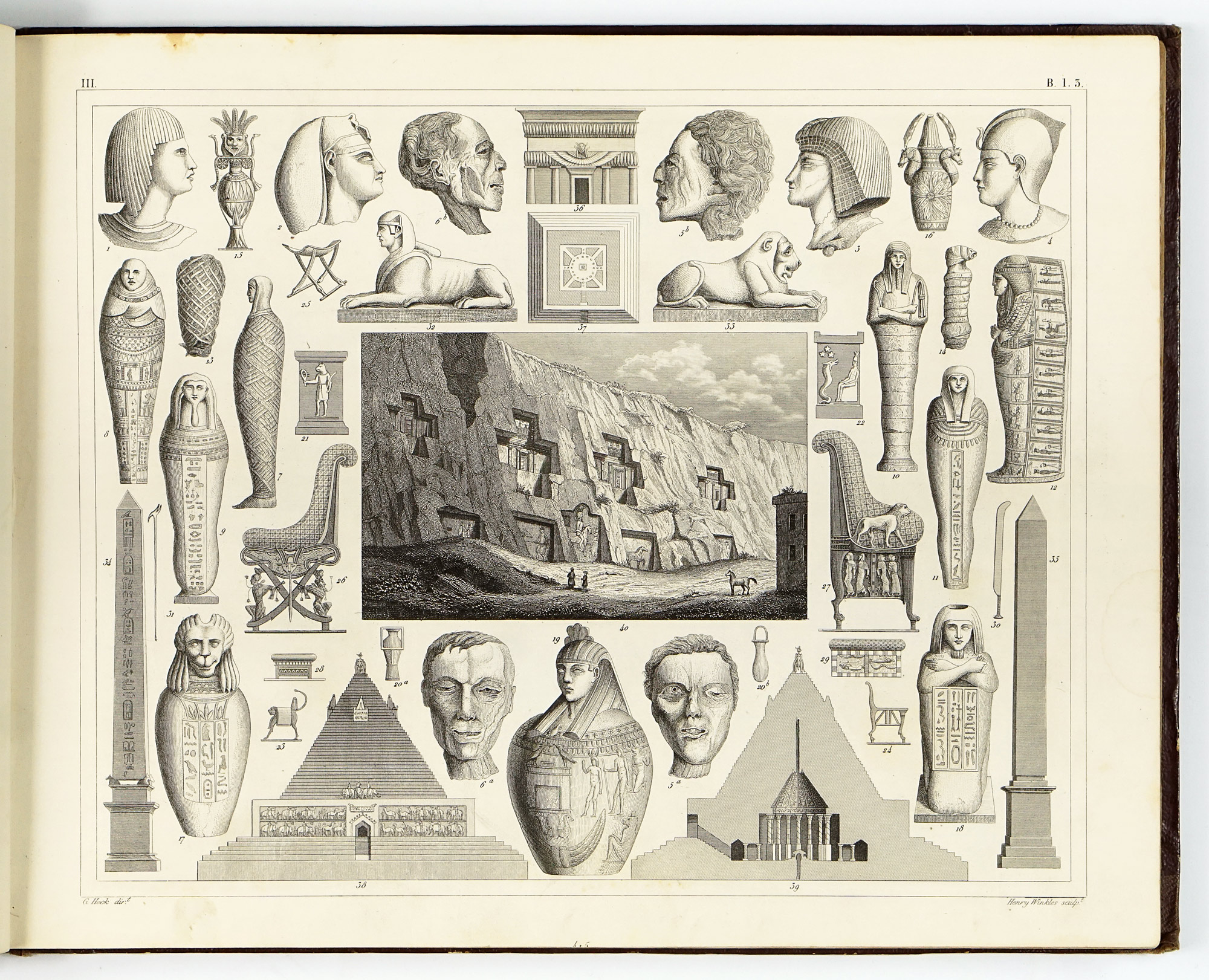

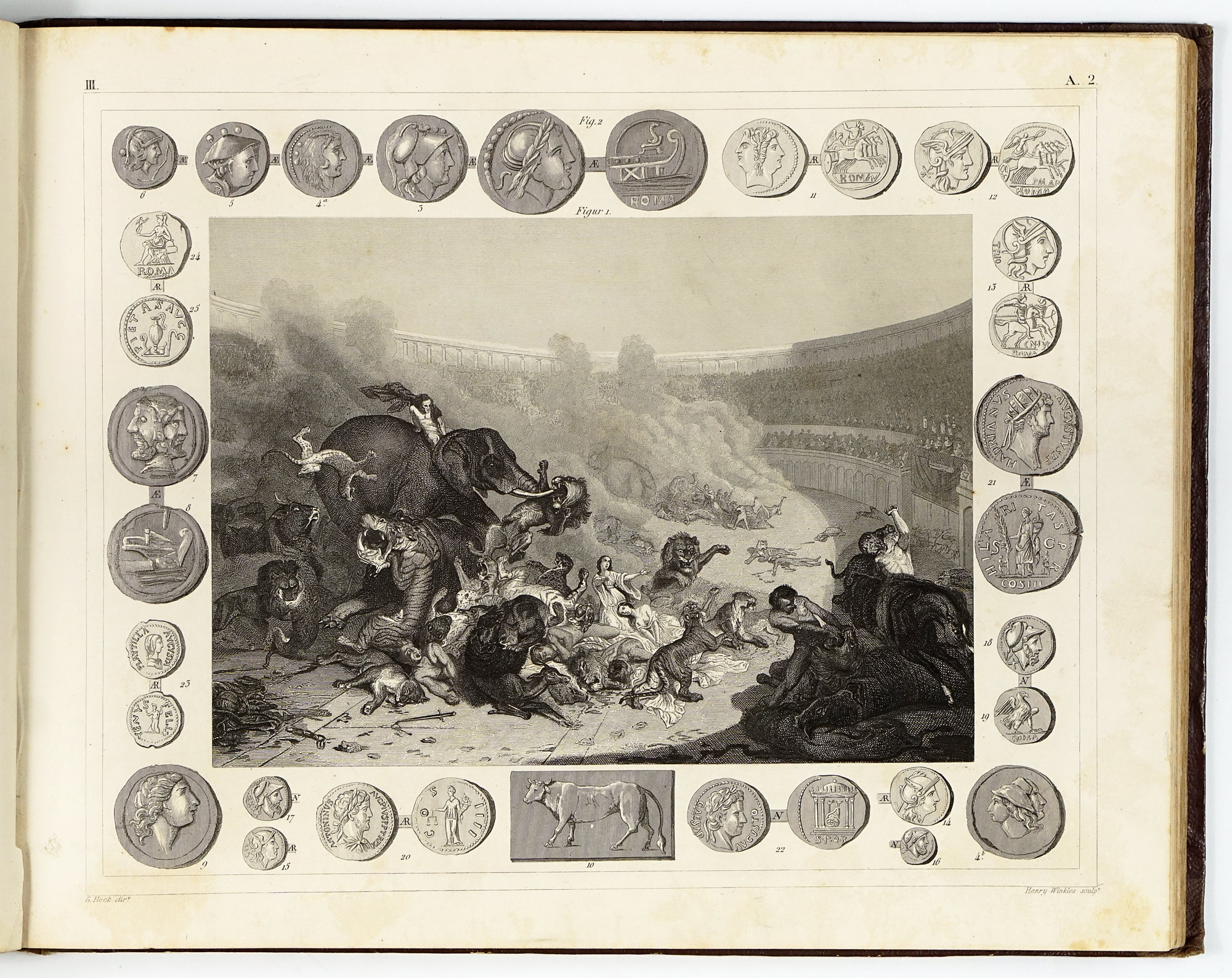

Part III: History and Ethnology — 39 plates

The third part addresses the historical development of human societies alongside their cultural and ethnological characteristics. It focuses on the Old World and medieval Europe, presenting history as a continuum shaped by peoples, territories, and material culture.

Plates devoted to the ancient and early historical Old World depict civilisations of the Near East, classical antiquity, and early European cultures. Maps, genealogical schemes, architectural reconstructions, and ethnographic figures combine to create a visual narrative of cultural origins and interactions. These images reflect the period’s fascination with antiquity as the foundation of European civilisation.

Medieval plates illustrate the transformation of the ancient world into medieval Europe. Feudal structures, territorial divisions, religious institutions, and characteristic material culture are rendered visually accessible. Costumes, weapons, and architectural forms are commonly used as markers of identity and historical change, revealing how the Middle Ages were interpreted through a combination of scholarship and romantic historicism.

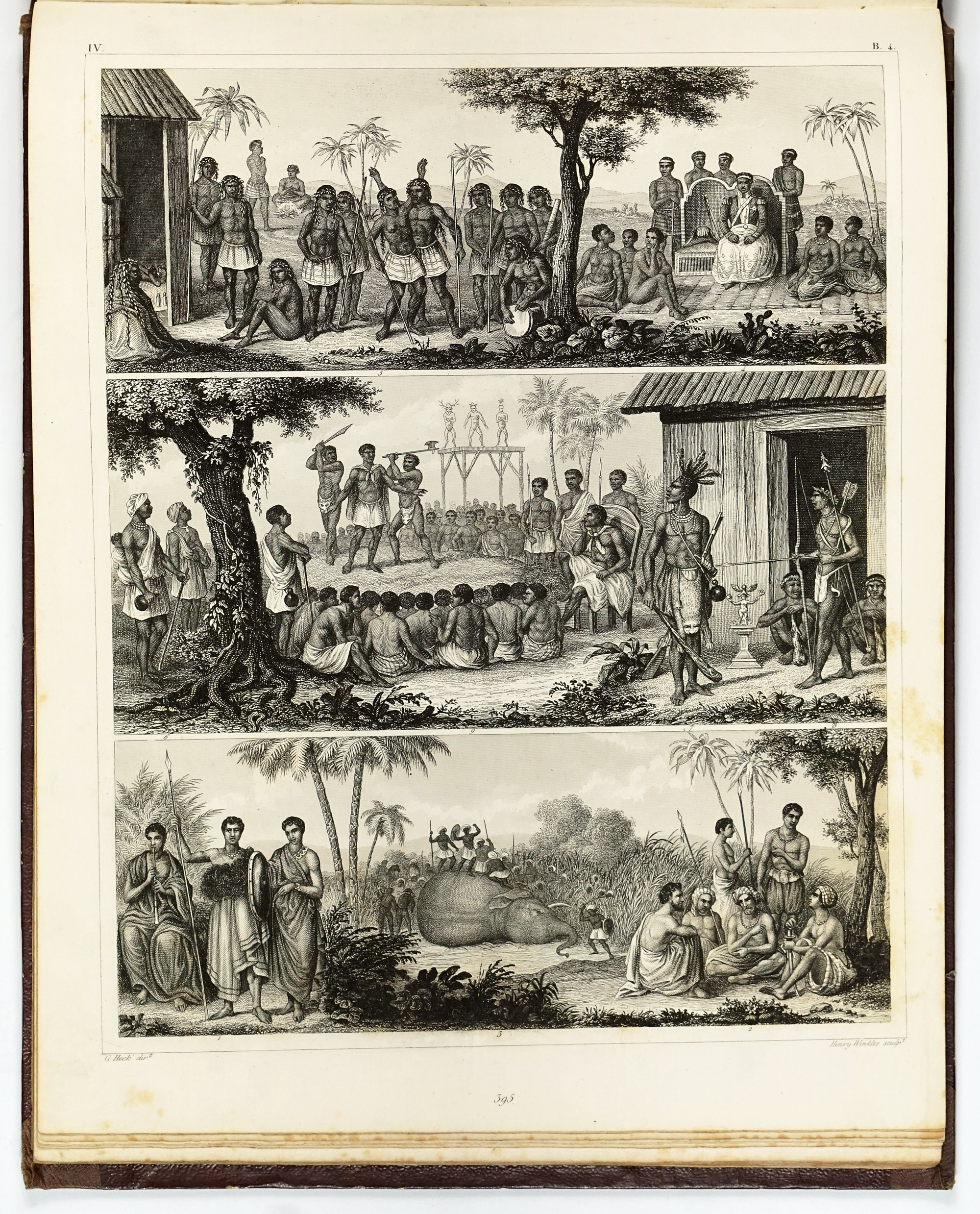

Part IV: Contemporary Ethnology — 42 plates

The fourth part is among the most visually striking sections of the entire atlas. Devoted to contemporary ethnology, it seeks to catalogue the peoples of the world as they were understood in the mid-19th century, primarily through costume, physical appearance, and material culture.

Arranged by continent, these plates present comparative figures of “types,” typically shown in traditional dress and posed to emphasize perceived cultural characteristics. Europe and Asia is treated with particular detail and internal differentiation, while Africa, the Americas, and Oceania are presented in broader, often generalized groupings.