The Bilder-Atlas zum Konversations-Lexikon represents one of the most ambitious attempts of the 19th century to translate contemporary scientific knowledge into a coherent visual language. Issued here in its first edition, the atlas was conceived and edited by Johann Georg Heck and published by the renowned Leipzig house of F. A. Brockhaus. It was designed as an illustrated companion to the Brockhaus Konversations-Lexikon, the most influential German encyclopedia of its time, and established a visual standard that would shape later encyclopedic atlases and pictorial reference works.

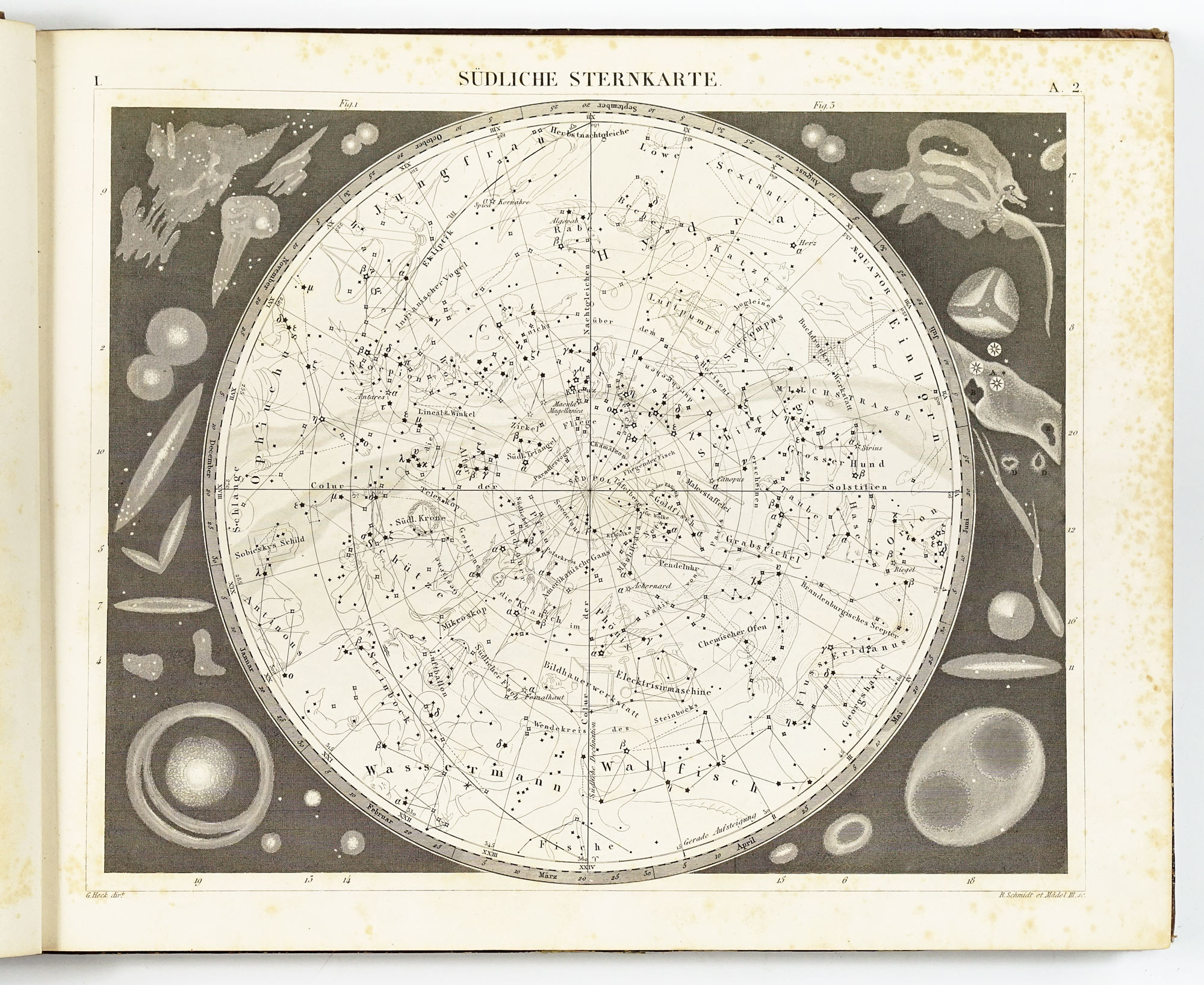

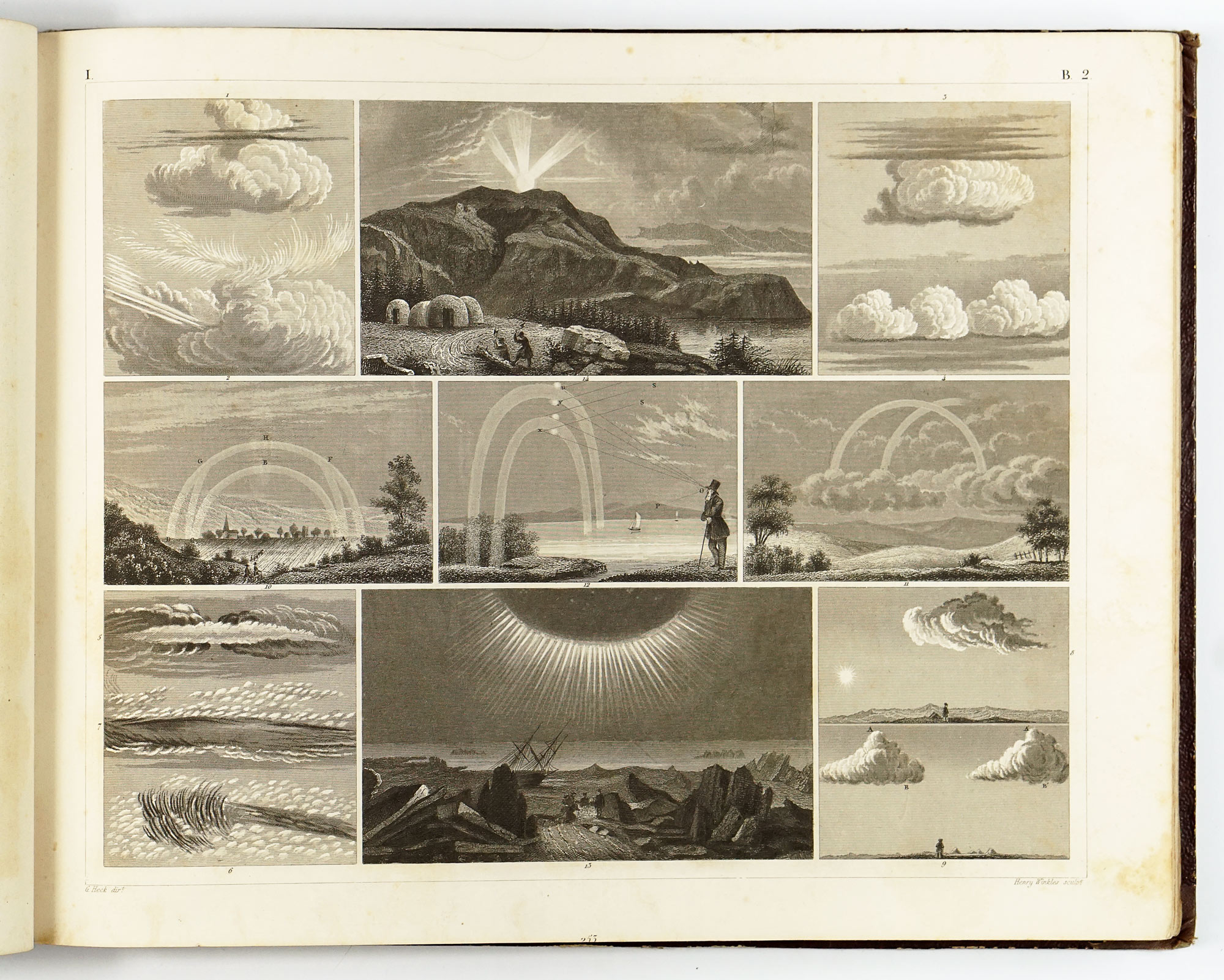

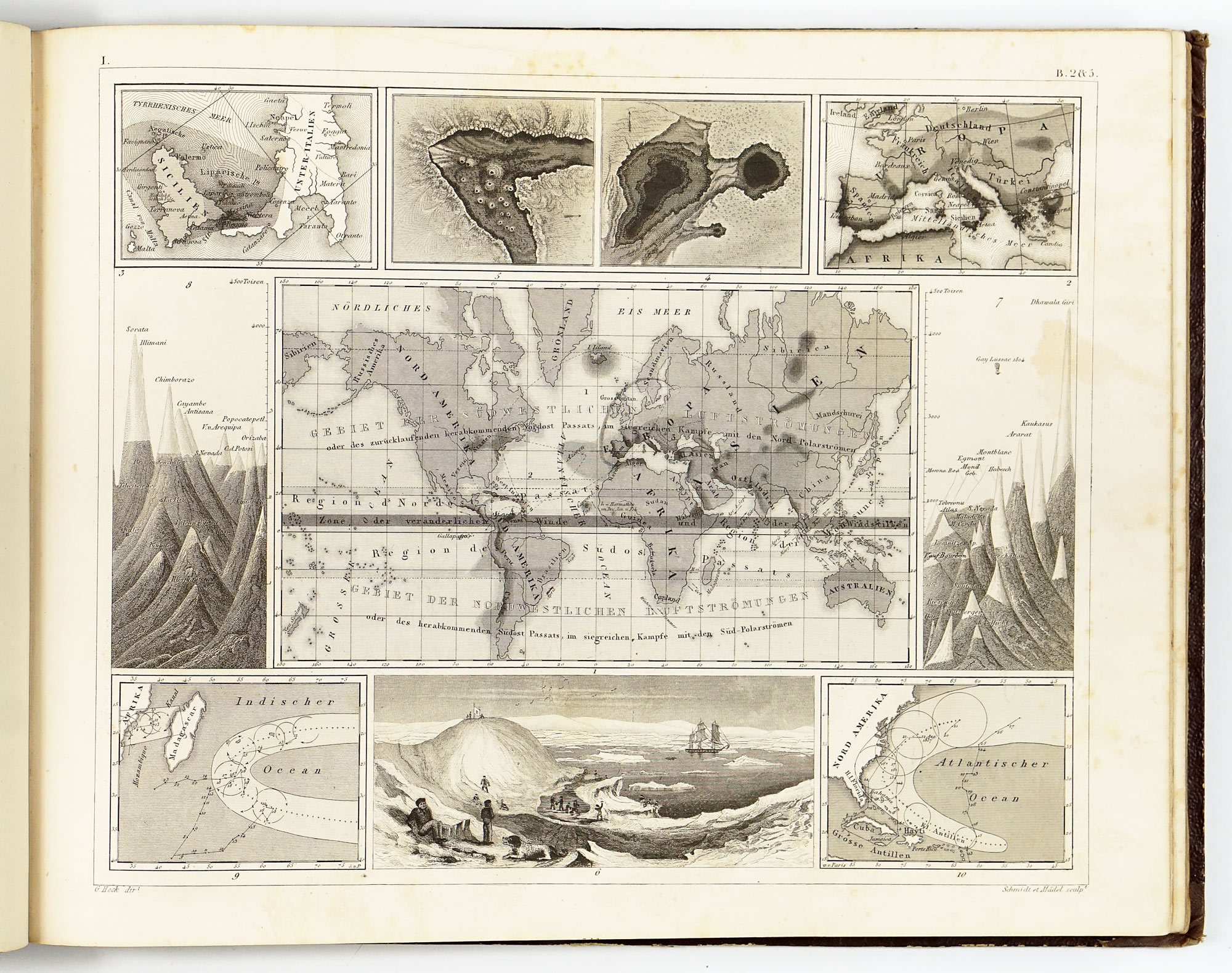

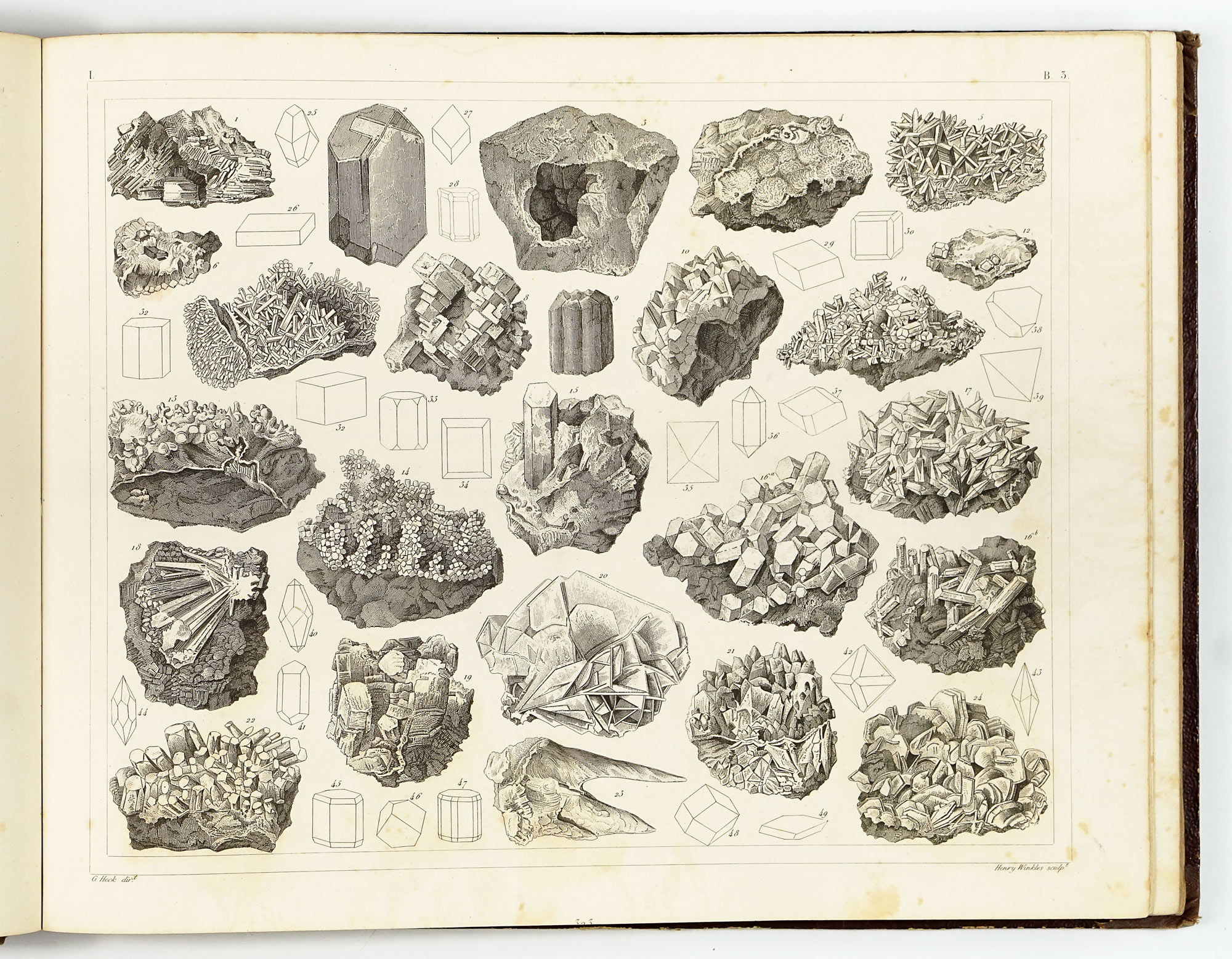

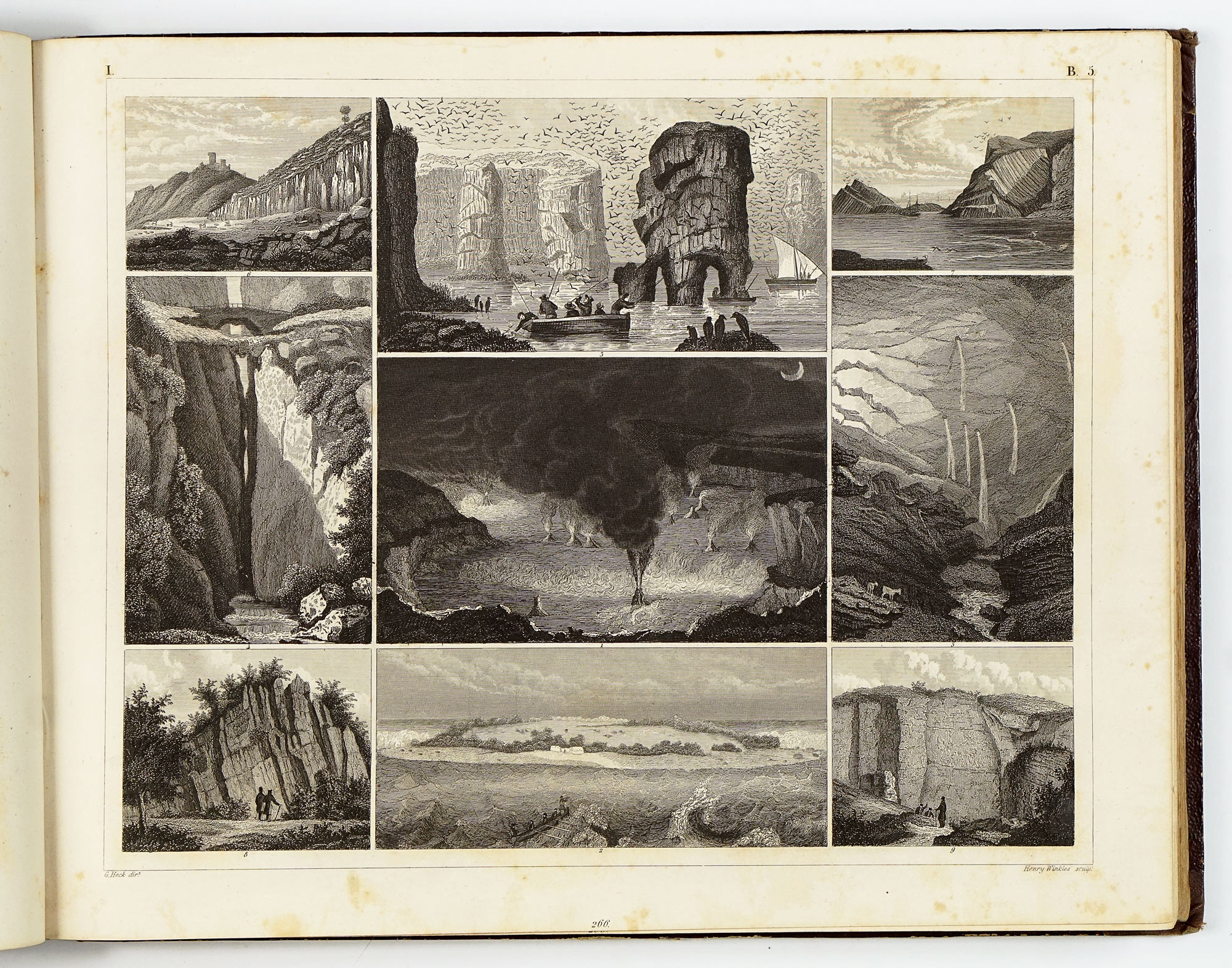

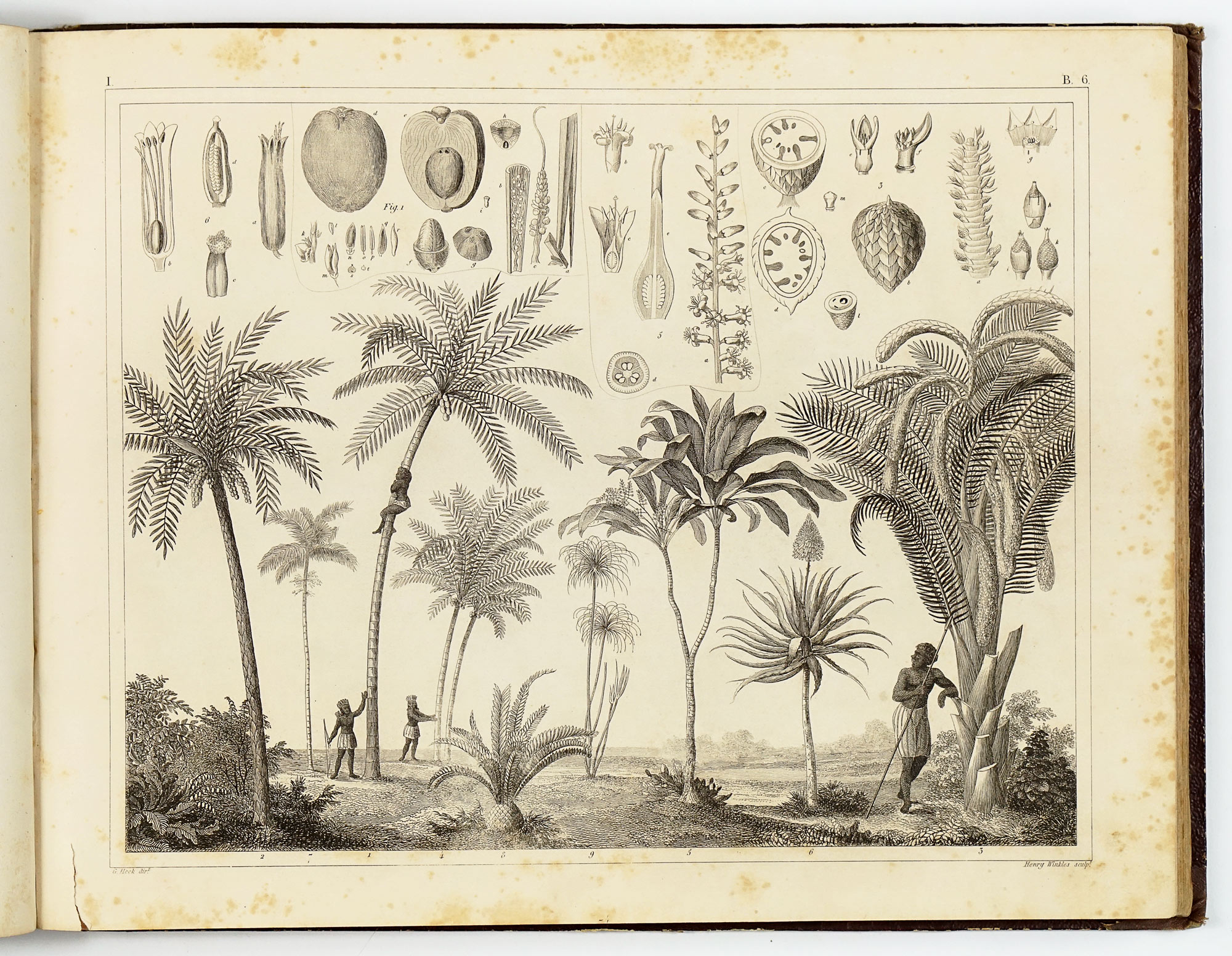

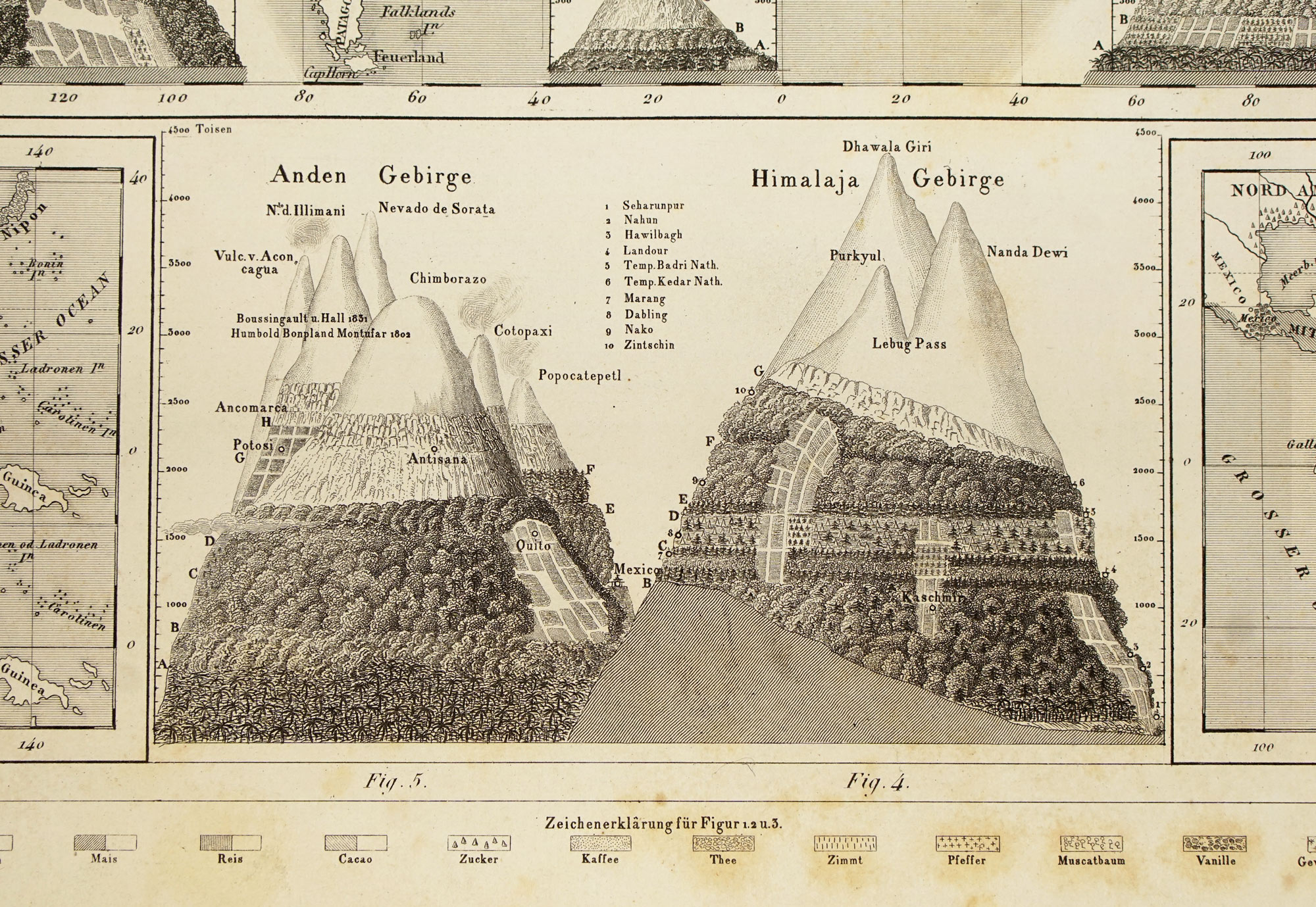

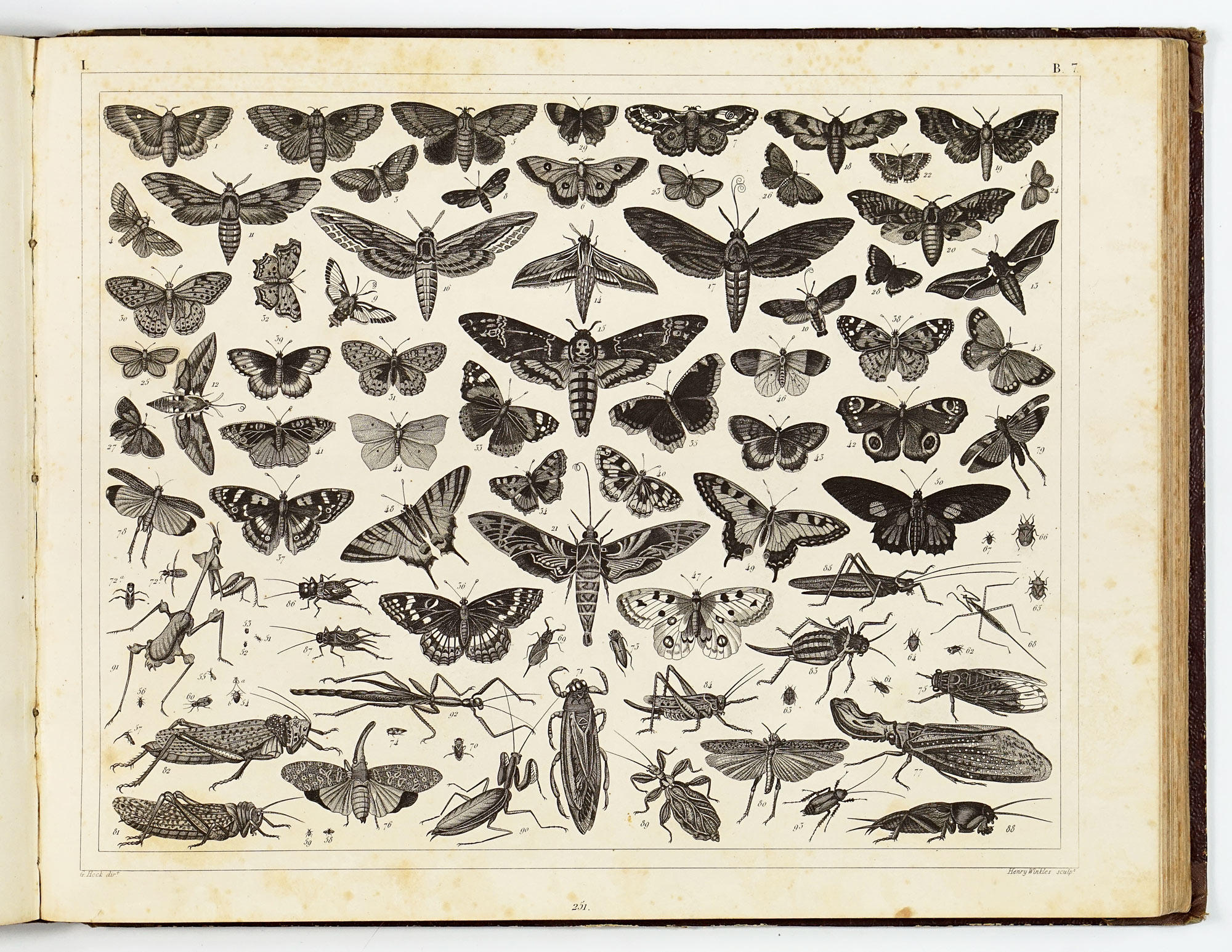

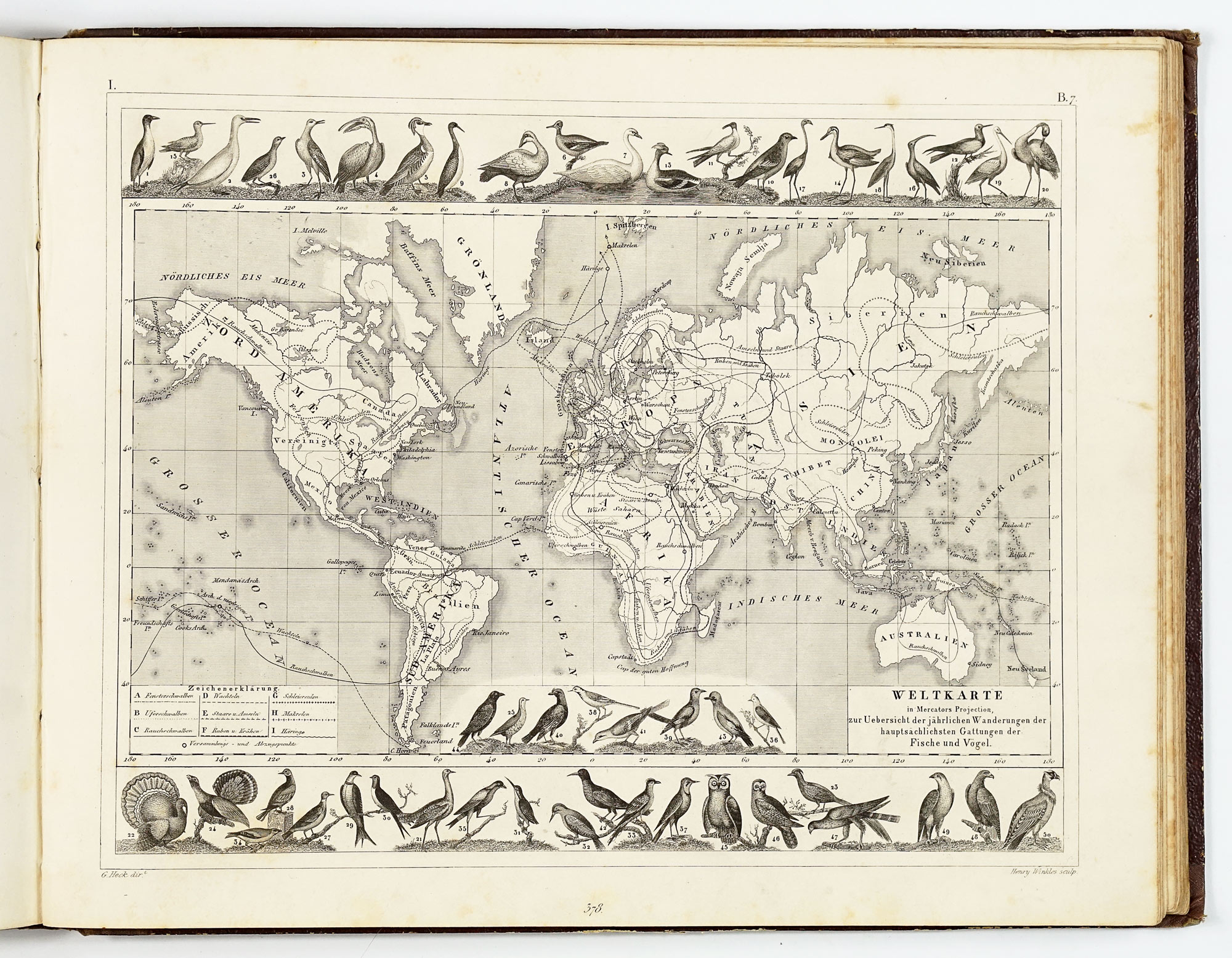

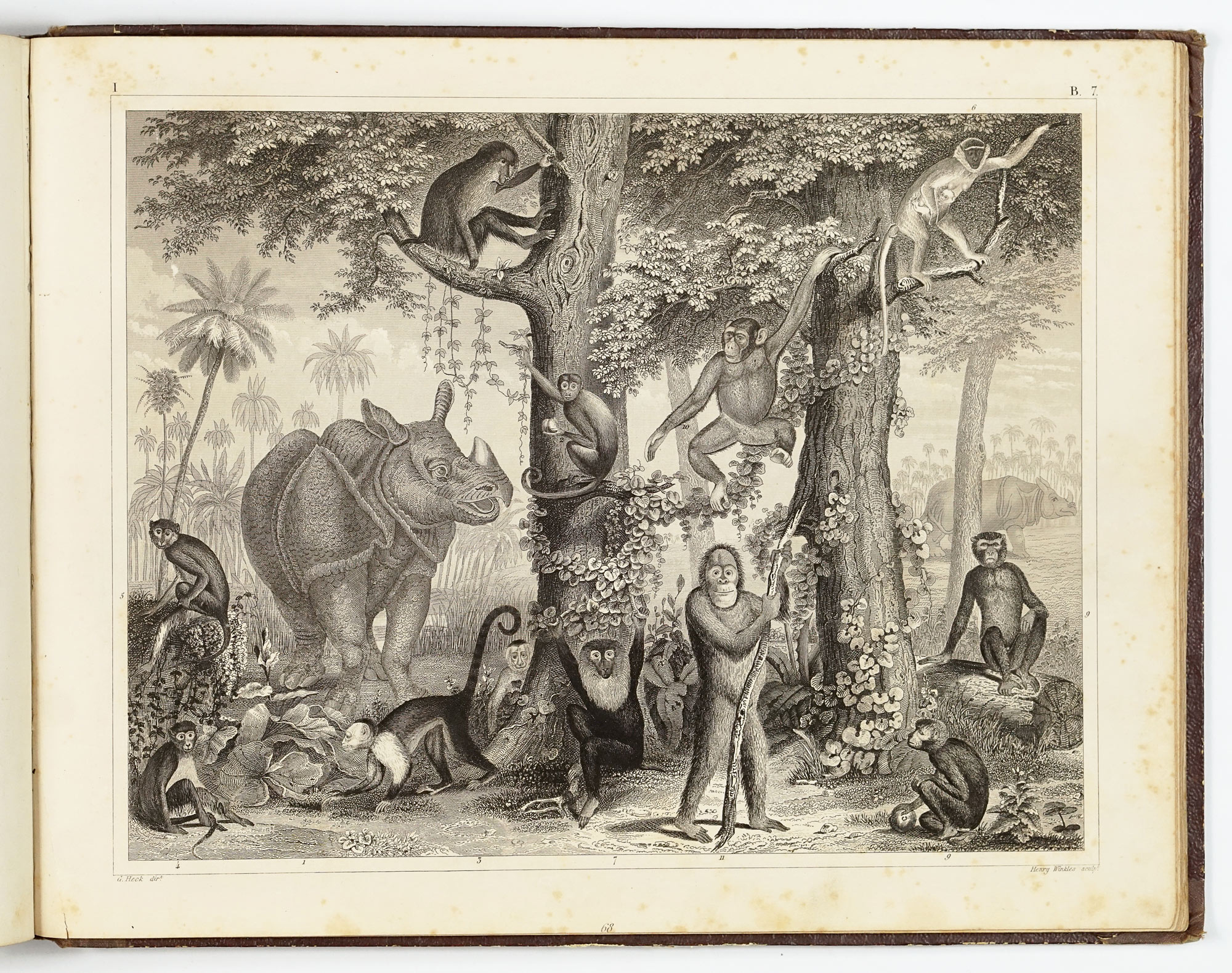

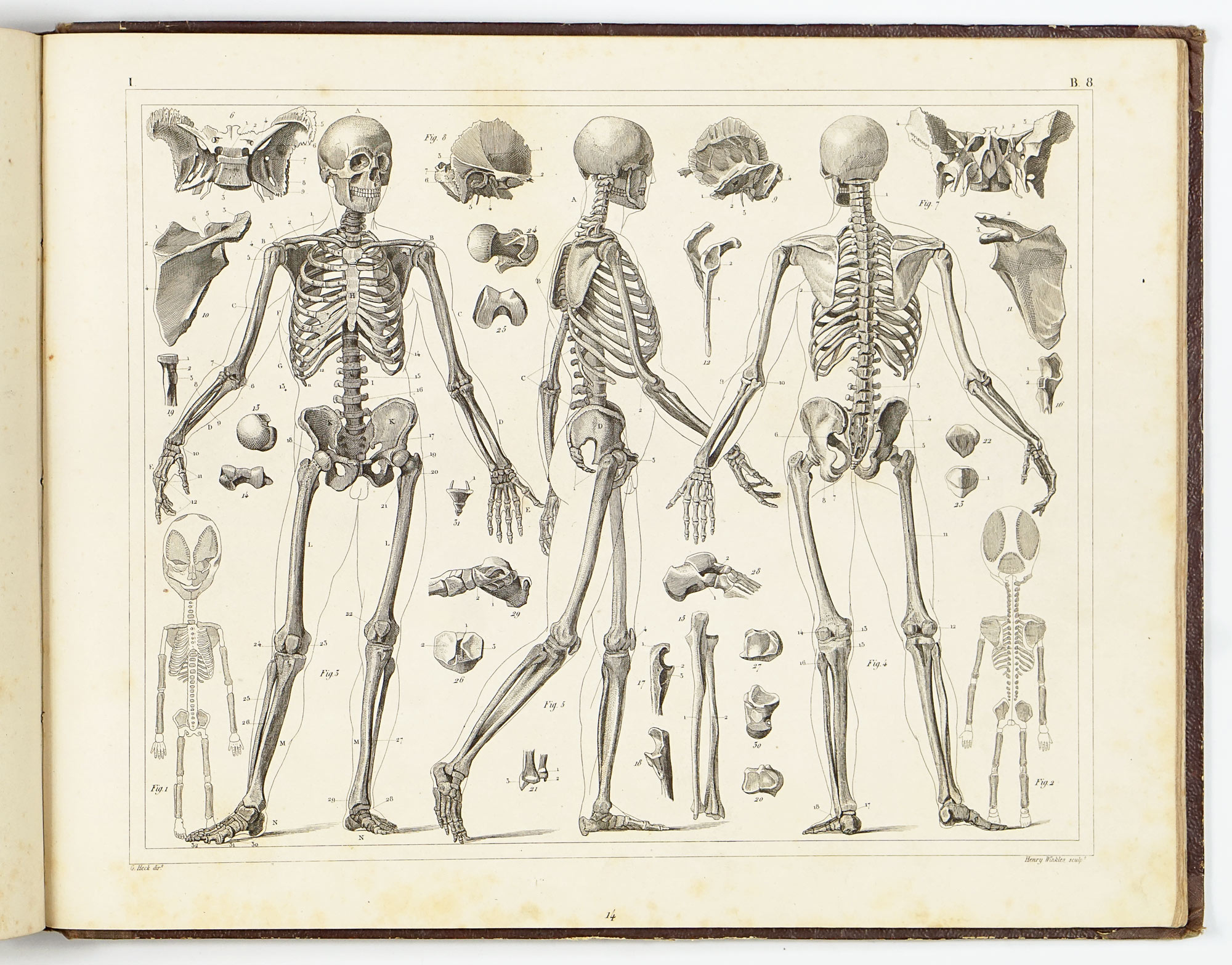

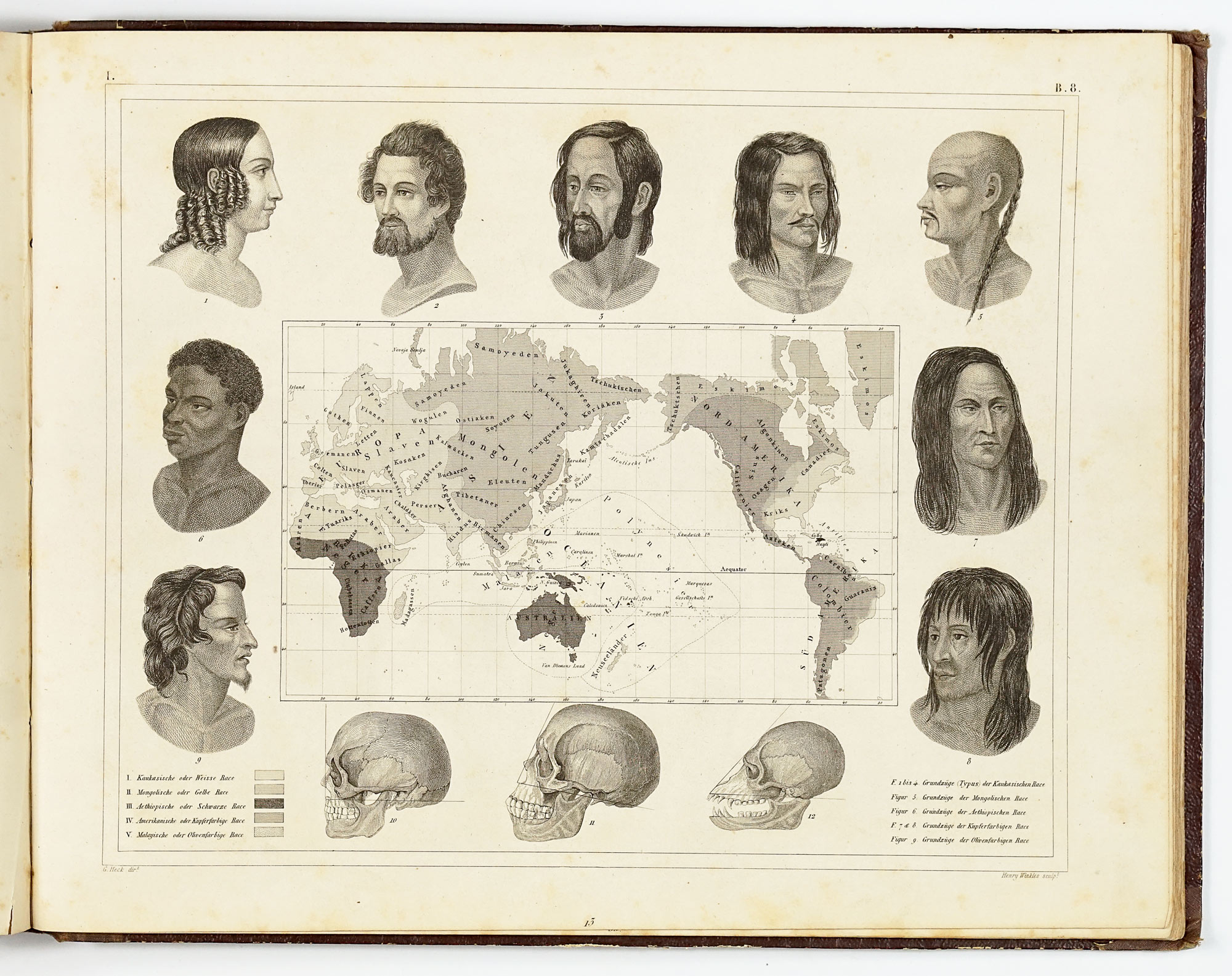

Rather than functioning as a geographical atlas in the narrow sense, the Bilder-Atlas functions as an 'iconographic encyclopedia': a systematic collection of engraved plates intended to visualize the entirety of human knowledge. The present Erste Abtheilung (First Part), devoted to Mathematics and the Natural Sciences, forms the scientific foundation of the entire project and comprises an impressive total of 141 plates.

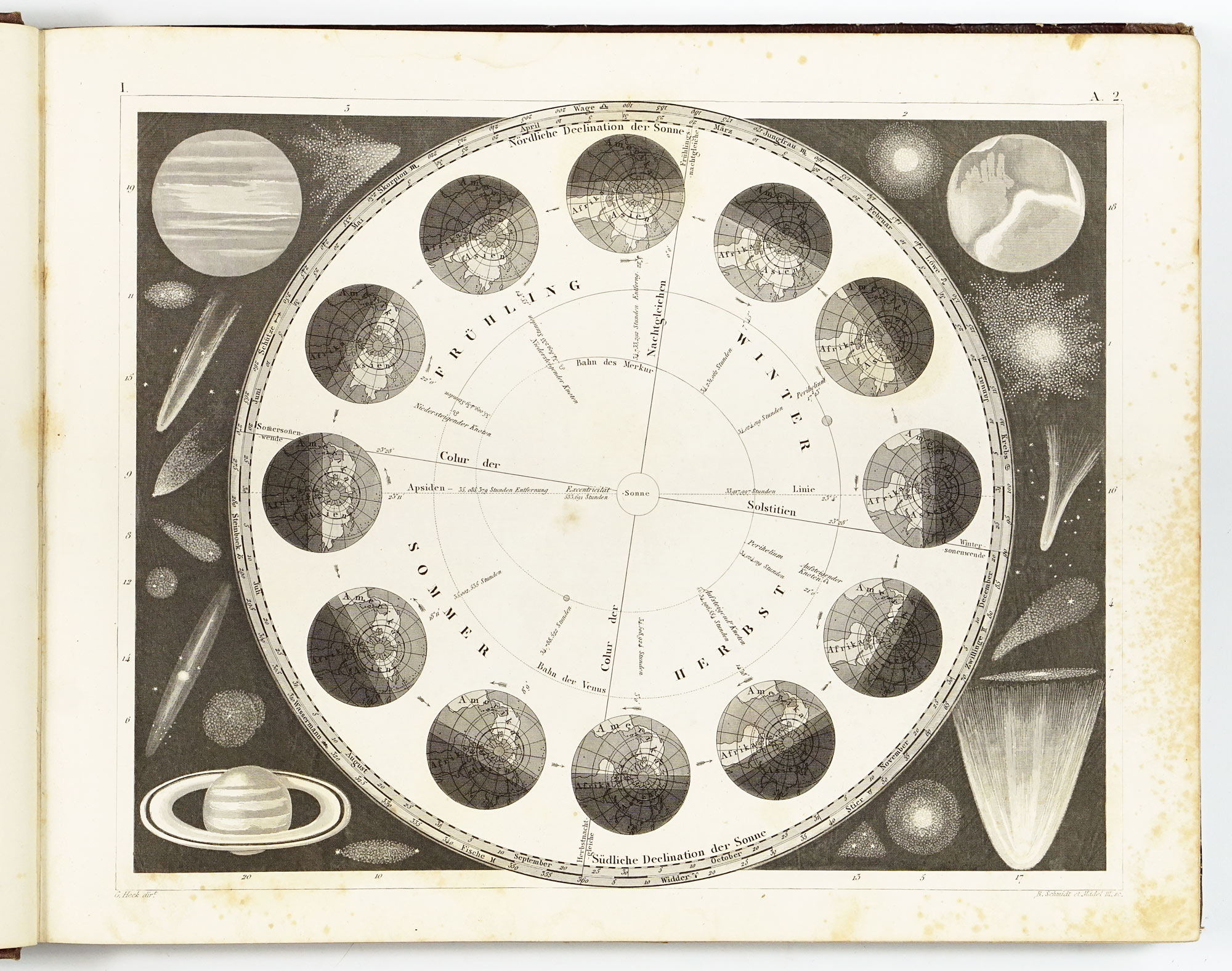

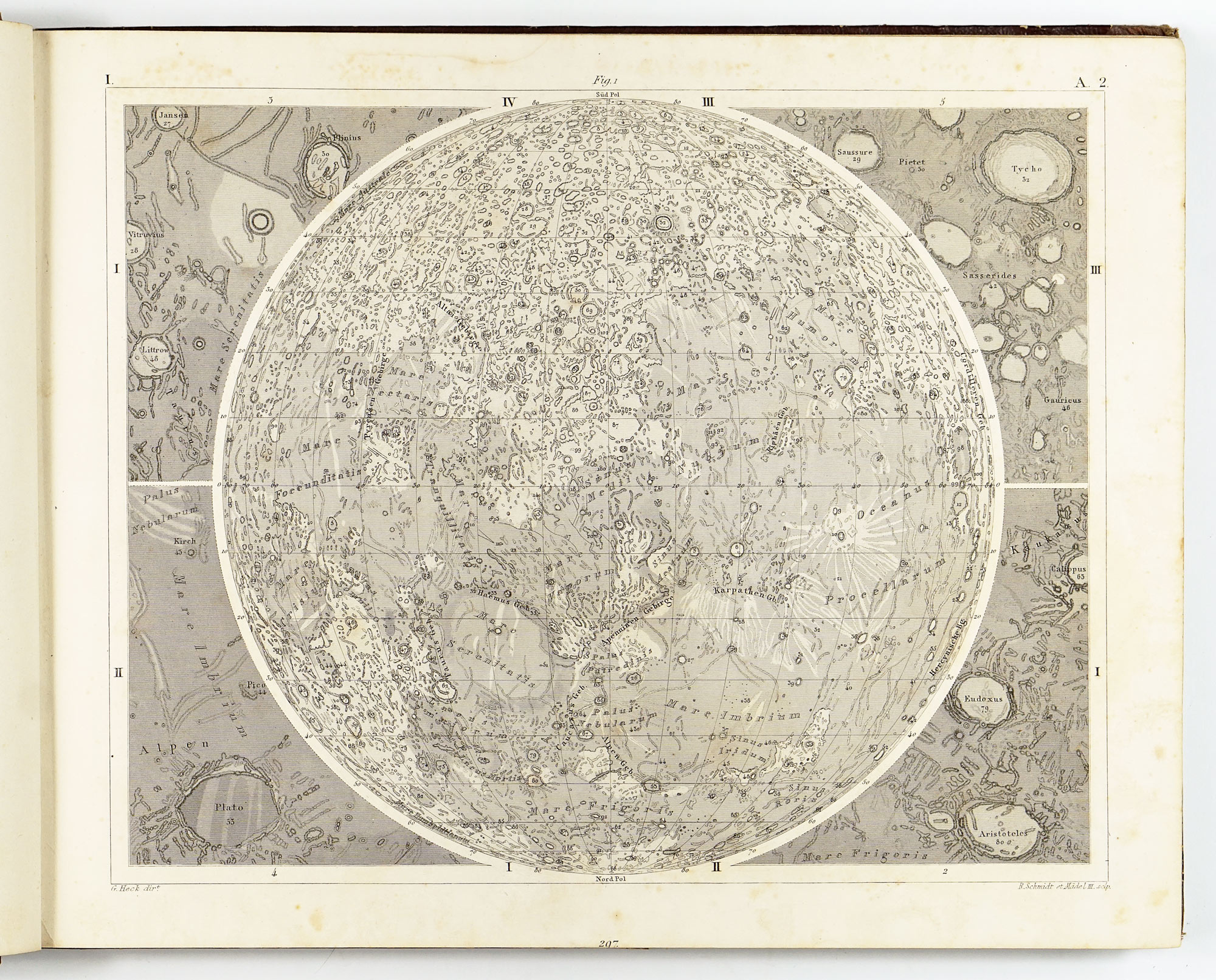

The atlas covers broad spectrum of disciplines: mathematics, astronomy, physics, meteorology, chemistry, mineralogy, geology and geognosy, botany, zoology, anthropology, and even surgery. Zoology alone accounts for 46 plates, while botany and anthropology are also richly illustrated, reflecting the period’s intense interest in classification, morphology, and comparative study.

The plates were not originally issued in systematic order. Instead, they were published in installments that deliberately mixed subjects, ensuring that each delivery offered visual material from several of the ten principal sections. This publishing strategy was both practical and commercial, sustaining public interest over time while accommodating the realities of engraving and production.

Only once the textual portion of the first section was completed were readers instructed to rearrange the plates according to a strict scientific order. The accompanying plate list therefore plays a crucial role: the large numbers correspond to the engraved plate numbers themselves, while the smaller numbers indicate the correct systematic sequence. This dual numbering system is characteristic of large 19th-century encyclopedic projects.

The preface offers unusually explicit guidance on how the atlas was meant to be used. Binding the plates into a single volume was explicitly discouraged. Instead, readers were advised to group plates by section and store them between cardboard covers with bands, allowing for flexible consultation alongside separately bound text volumes. This practical, modular approach underscores the atlas’s intended role as a working reference tool rather than a purely decorative book.

The plates themselves are finely engraved and typographically disciplined, combining clarity with density of information. Diagrams, sectional views, comparative tables, and carefully labeled figures dominate, reflecting the didactic ideals of the period. The emphasis is not decorative but explanatory: each image is designed to be read alongside the encyclopedia text, reinforcing understanding through visual comparison.

As a result, complete and correctly arranged sets are today relatively uncommon. Plates were often separated, rebound, or dispersed over time, making intact examples with all 141 plates particularly desirable.

The Bilder-Atlas zum Konversations-Lexikon occupies a significant place in the history of scientific illustration and encyclopedic publishing. It embodies the Enlightenment ideal of universal knowledge made accessible through systematic organization and visual clarity. For collectors, historians of science, and bibliophiles, this first section stands as a testament to Brockhaus’s editorial ambition and to Johann Georg Heck’s skill in orchestrating one of the most comprehensive visual encyclopedias of the 19th century.