Published in 1899 by Archibald Constable and Co. under the patronage of the Royal Geographical Society, the Atlas of Meteorology stands as one of the most ambitious and influential scientific atlases of the late nineteenth century. Edited by J. G. Bartholomew and A. J. Herbertson and dedicated to Queen Victoria. The atlas forms part of the ambitious multi-volume series Bartholomew’s Physical Atlases and represents its third volume. Of the remaining volumes, the Atlas of Zoogeography (labelled as the 5th volume) is the only other title known to us to exist.

As the preface makes clear, meteorology had long lagged behind other sciences in systematic cartographic representation. Dr. Julius Hann’s pioneering Atlas of Meteorology of 1887—issued as part of the Berghaus Atlas—was acknowledged as the first serious attempt to map atmospheric science. Yet in the dozen years that followed, the explosion of global observations, the institutionalization of national meteorological services, and the practical demands of navigation, agriculture, and empire created an urgent need for a far more comprehensive work. Bartholomew and Herbertson’s atlas was conceived precisely to meet that moment, aiming to represent “the position of meteorology at the close of the nineteenth century.”

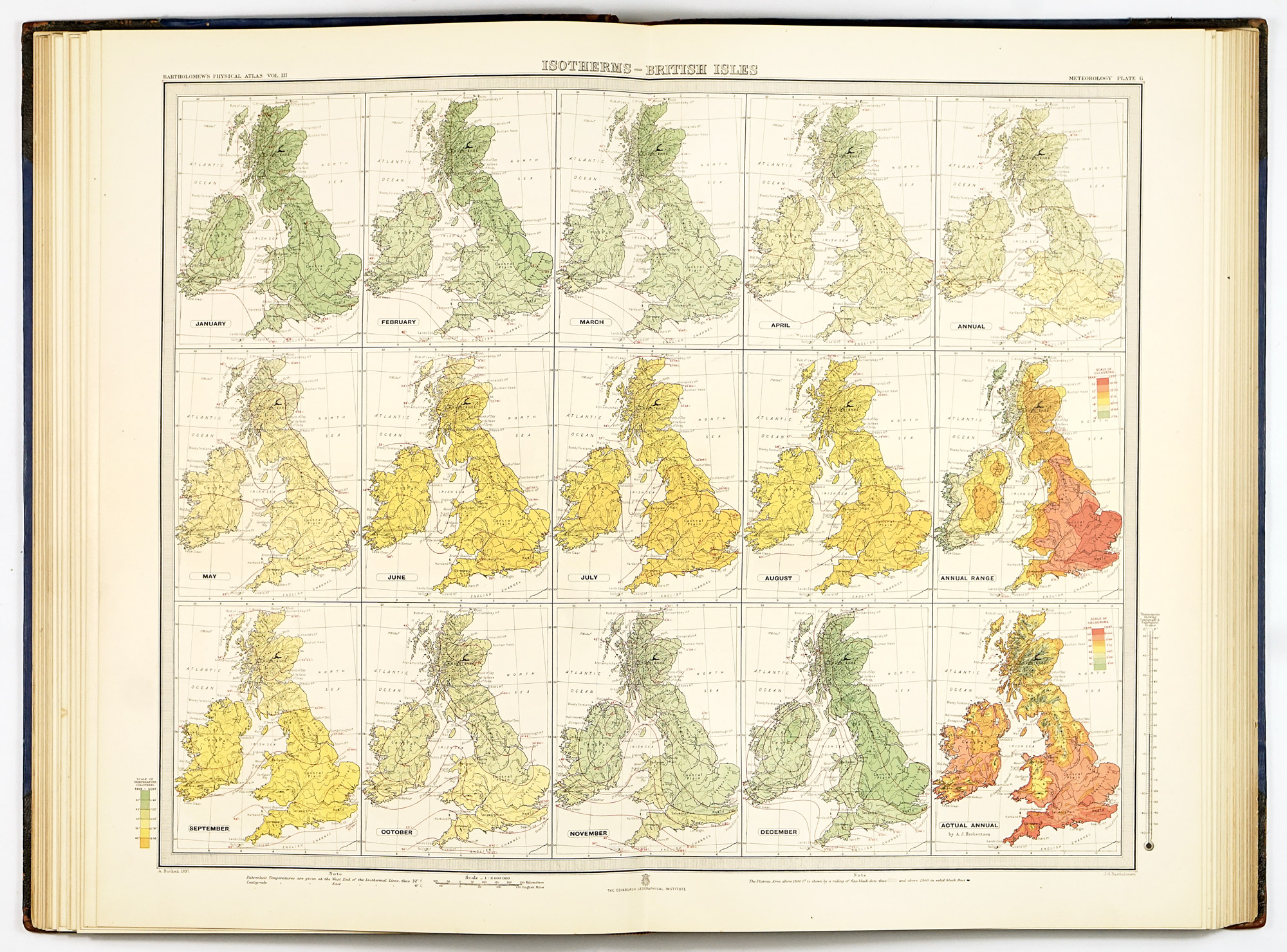

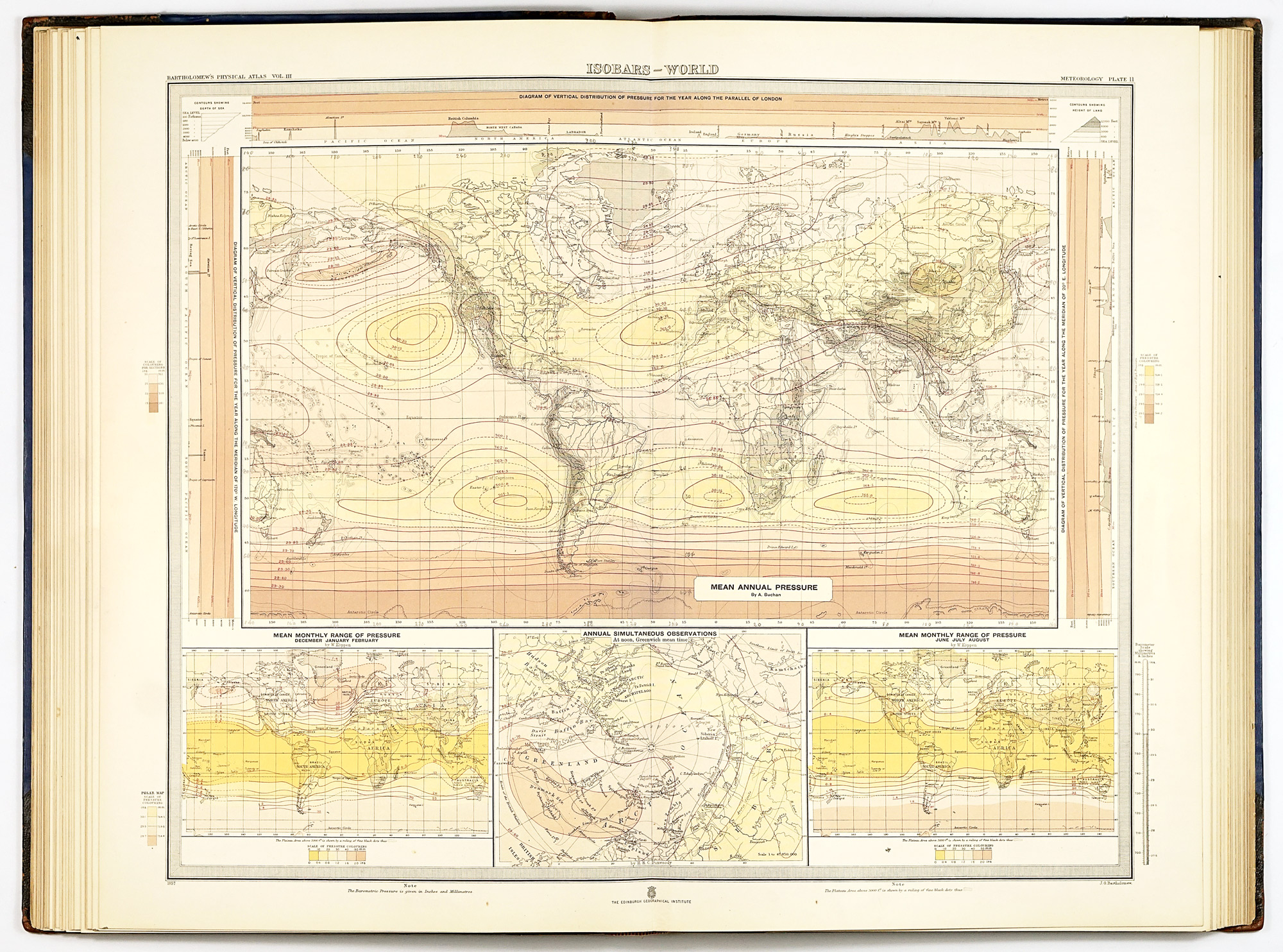

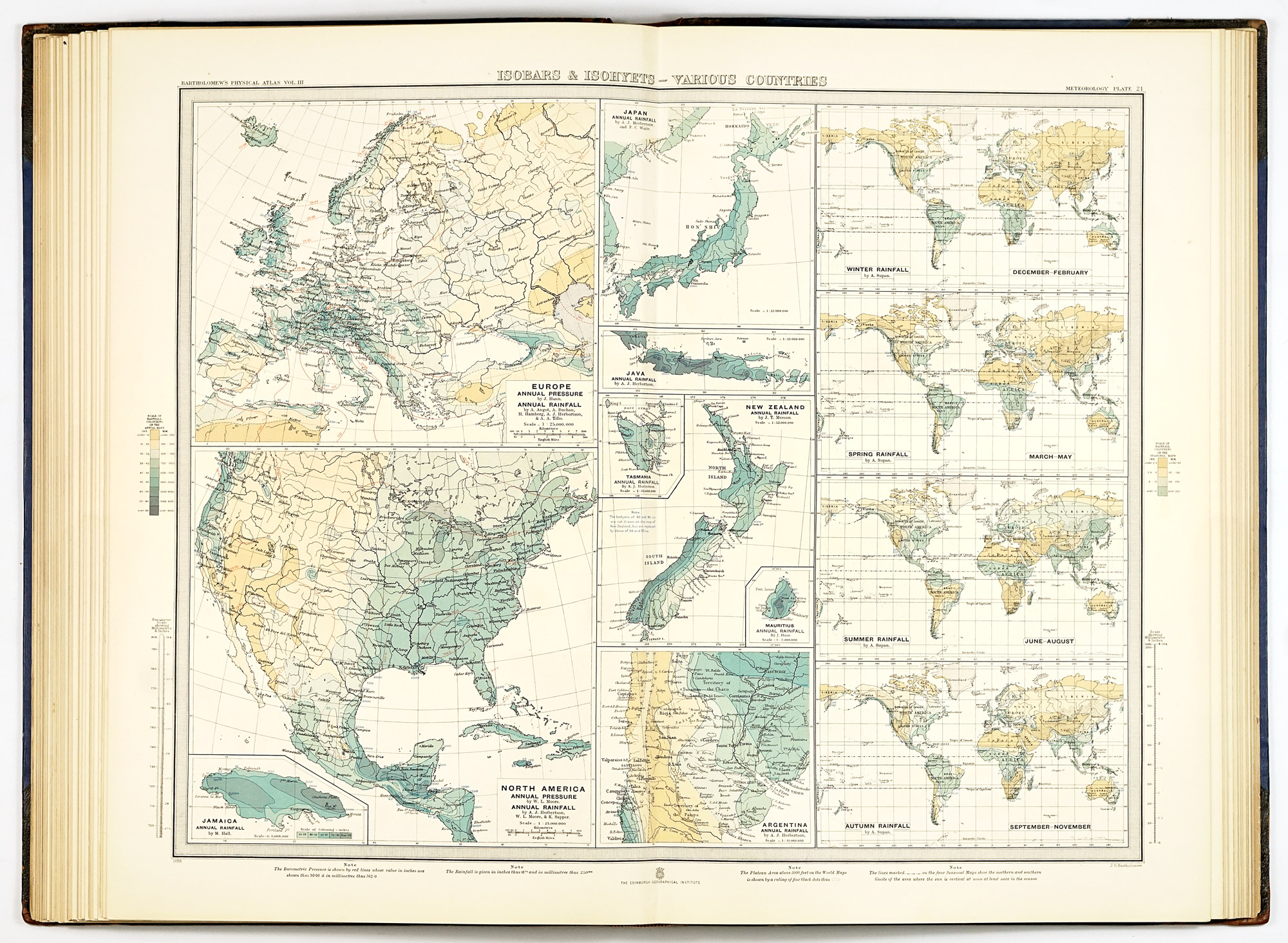

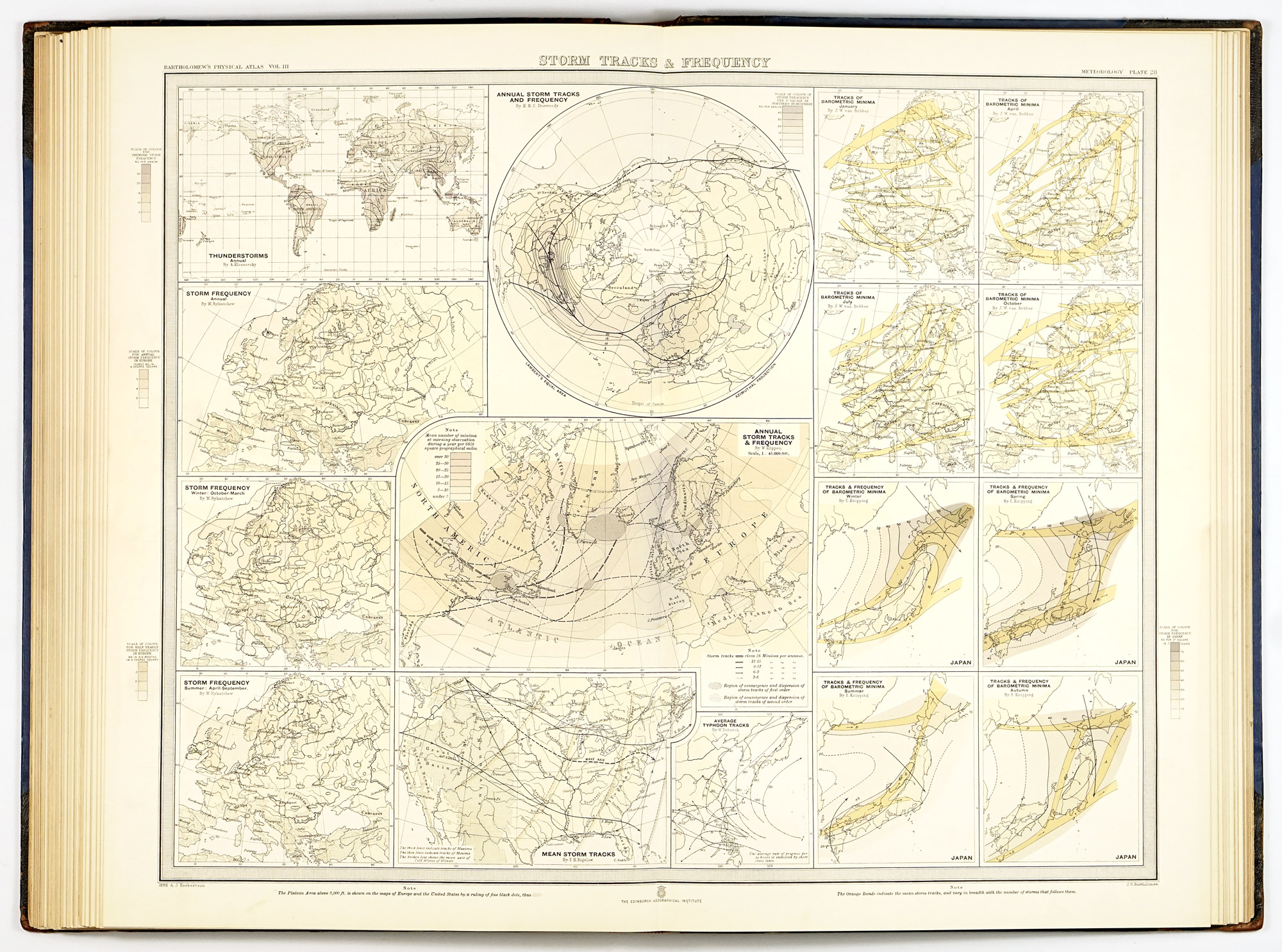

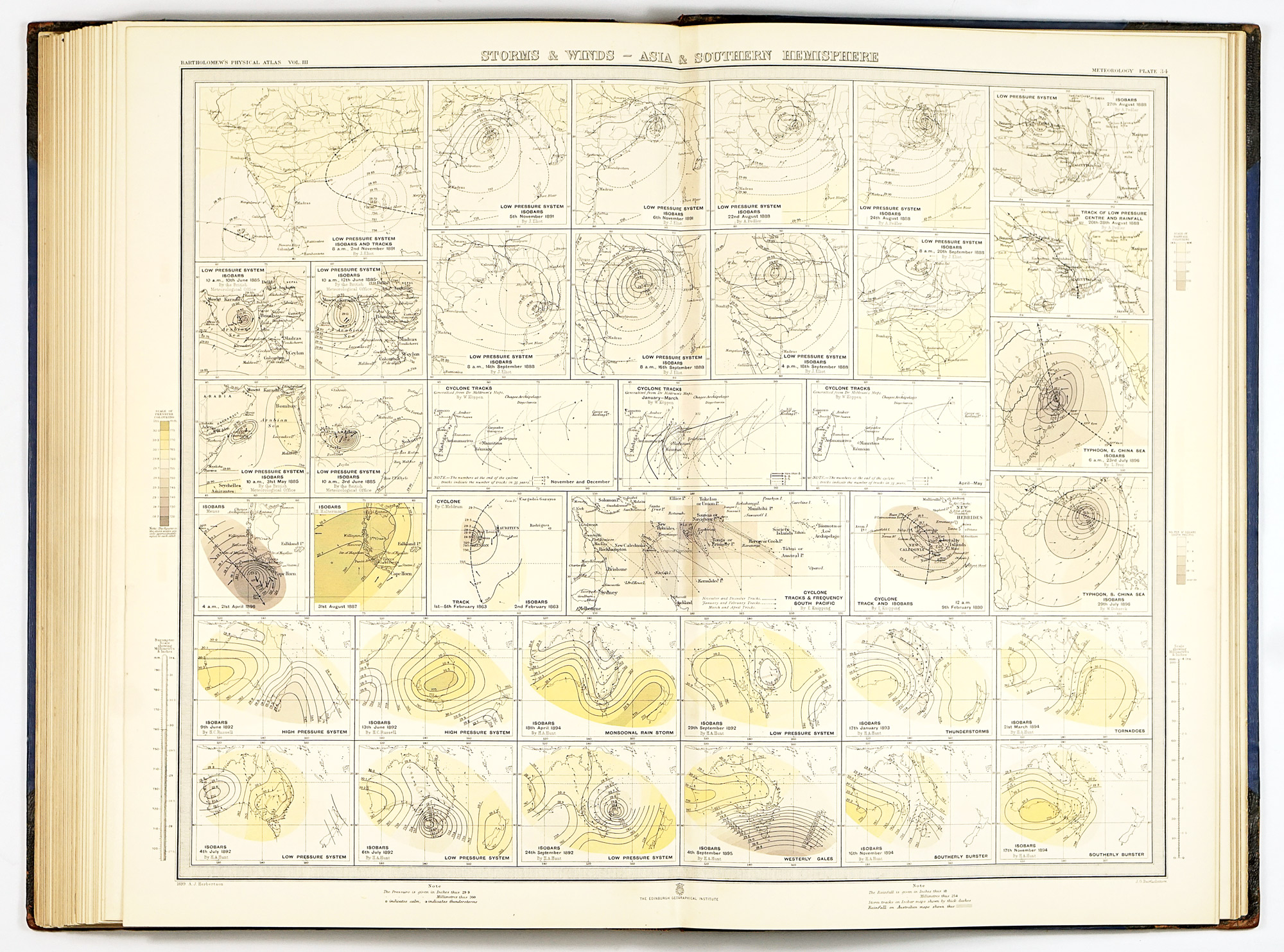

The scope of the atlas is organised into two principal sections: Climate and Weather. The climate maps synthesise vast quantities of observational data, presenting monthly and annual distributions of temperature, pressure, winds, cloud cover, sunshine, and rainfall. These are shown first on a global scale and then, where data density permits, in enlarged regional and national treatments. The weather maps, together with seasonal and storm charts, shift the focus from averages to dynamics, illustrating characteristic weather types over defined regions and periods.

The explanatory texts guide the reader through the major patterns and causal relationships depicted on the maps. These include a compiled list of meteorological services and stations worldwide. A critical bibliography, glossary of meteorological terms, comparative tables, and a comprehensive index further underline the atlas’s role as both reference work and teaching tool.

Cartographically, the atlas exemplifies the highest standards of late Victorian mapmaking. Coverage is not evenly distributed across the globe: the clearest emphasis lies on Europe, the British overseas territories—most notably India, Australia, and South Africa—as well as the United States and Canada, reflecting both the availability of observational data and the geopolitical priorities of the period. The systematic use of the metric system alongside traditional English scales reflects an awareness of international scientific practice, while the disciplined application of uniform color gradations for different meteorological phenomena ensures clarity and comparability across hundreds of plates. This visual consistency, difficult to maintain at such scale, is one of the atlas’s greatest strengths and a hallmark of Bartholomew’s school.

Among the most notable and unusual features of the atlas is a series of plates devoted to anomalous weather patterns and storm situations across different parts of the world. These maps illustrate exceptional and extreme conditions and underscore the editors’ ambition to capture not only climate but the dynamic behaviour of the atmosphere.

The Atlas of Meteorology is also a testament to international scientific collaboration. The editors openly acknowledge their reliance on a wide network of leading authorities, including Hann, Köppen, van Bebber, Angot, and Willis L. Moore, among many others. The Royal Geographical Society’s decision to allow publication under its patronage was more than ceremonial: it signaled official recognition of the atlas as a work of national (and indeed international) importance.

Seen today, the Atlas of Meteorology occupies a unique position at the intersection of science, cartography, and history. It captures meteorology at a pivotal moment, just before the advent of upper-air observations, satellites, and numerical forecasting would transform the discipline. For collectors, historians of science, and lovers of thematic cartography, it remains not only a masterpiece of nineteenth-century atlas production but also a powerful visual record of how the world’s climate and weather were first comprehensively mapped and understood on a global scale.