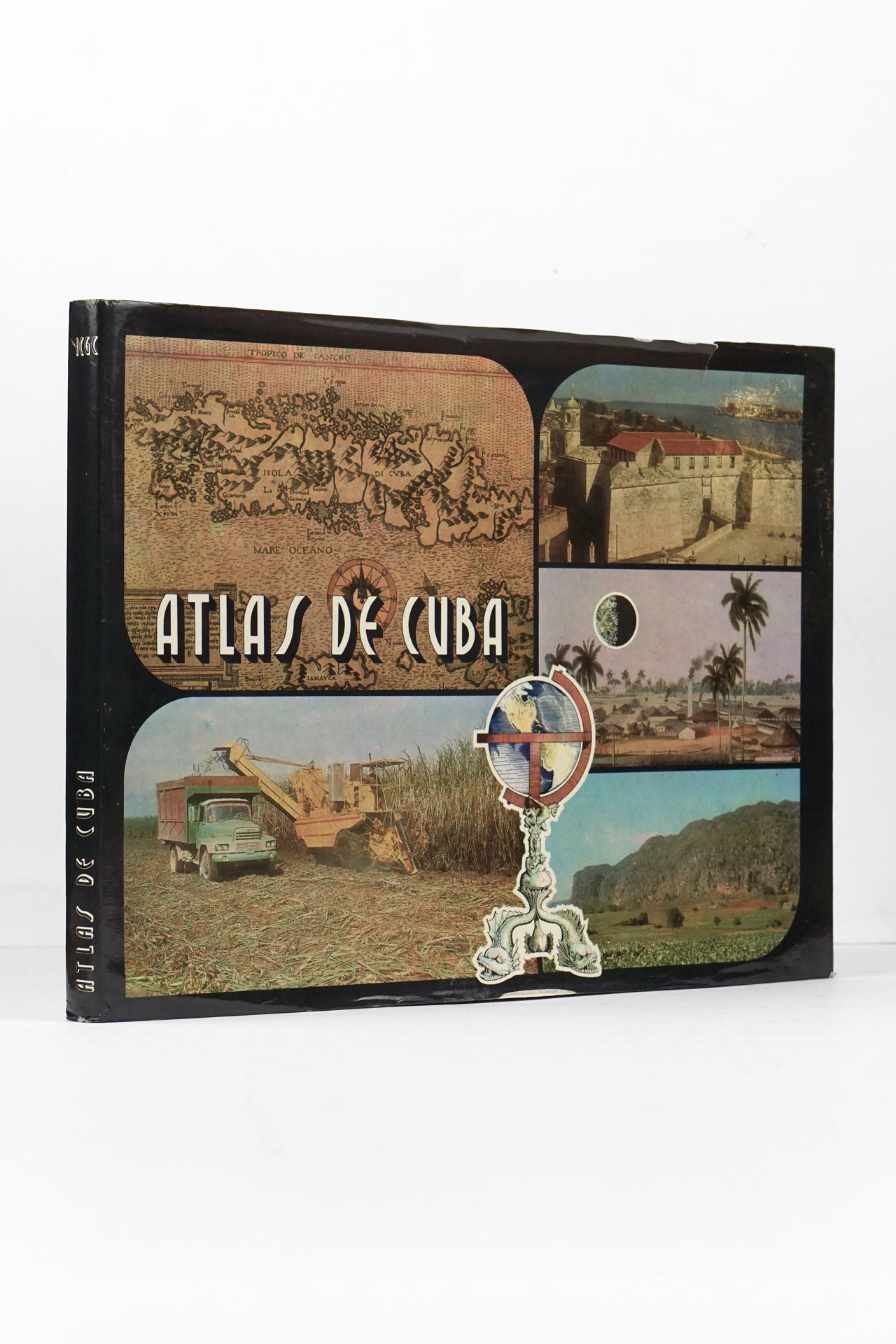

Published in 1978 by the Instituto Cubano de Geodesia y Cartografía under the leadership of Carlos Manuel Ibarra Martín, the Atlas de Cuba is a consciously commemorative and ideologically framed work, created to mark the twentieth anniversary of the triumph of the Cuban Revolution. One of its central objectives is to present, in cartographic form, the country’s achievements under the leadership of the Communist Party and the Socialist State, emphasizing the political, economic, social, and cultural transformations attributed to the revolutionary process since 1959.

Political and cultural context

The atlas emerged at a moment of institutional consolidation in Cuba. By the mid‑1970s, the revolutionary process had entered a phase of bureaucratic maturity: the Communist Party of Cuba had held its First Congress (1975), and the new Political‑Administrative Division of the country was implemented the same year. This reorganization—explicitly used as the cartographic basis of the atlas—was intended to rationalize economic planning and governance along socialist lines.

Within this context, the atlas functions as a state‑sanctioned narrative device. It reflects the worldview of a socialist state aligned with the Soviet bloc, not only through its ideological framing but also through its technical foundations: Soviet specialists are acknowledged for their methodological assistance, and the cartographic language follows Eastern Bloc conventions of thematic mapping, statistical abstraction, and didactic clarity.

Culturally, the work embodies the revolutionary ambition to democratize knowledge. The prologue explicitly identifies its intended audience as workers, peasants, students, intellectuals, and the general public. This ambition situates the atlas within the broader Cuban project of mass education, literacy, and cultural participation—an aim reinforced by the extensive use of photographs, graphs, and explanatory maps.

Structure and scope of the atlas

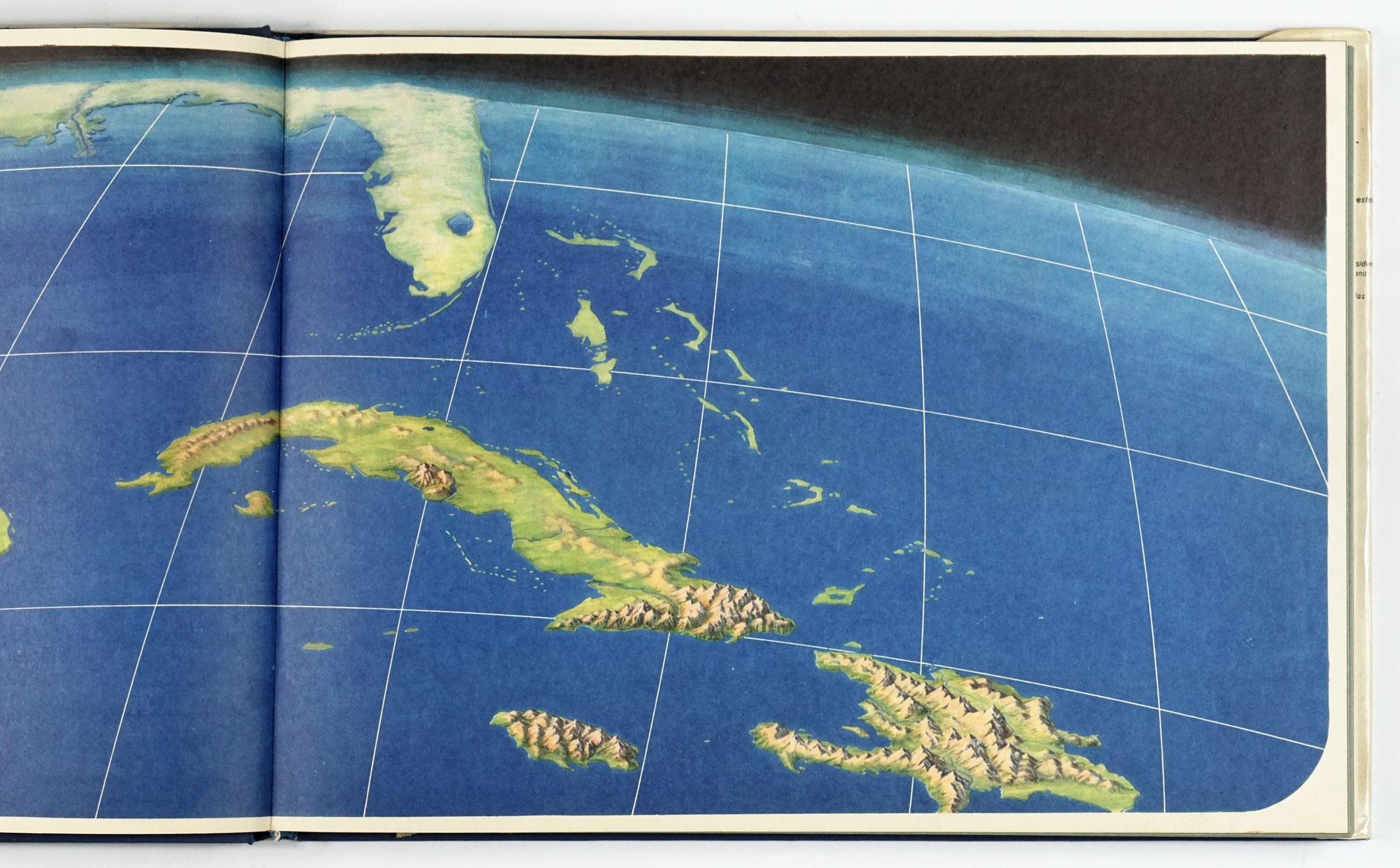

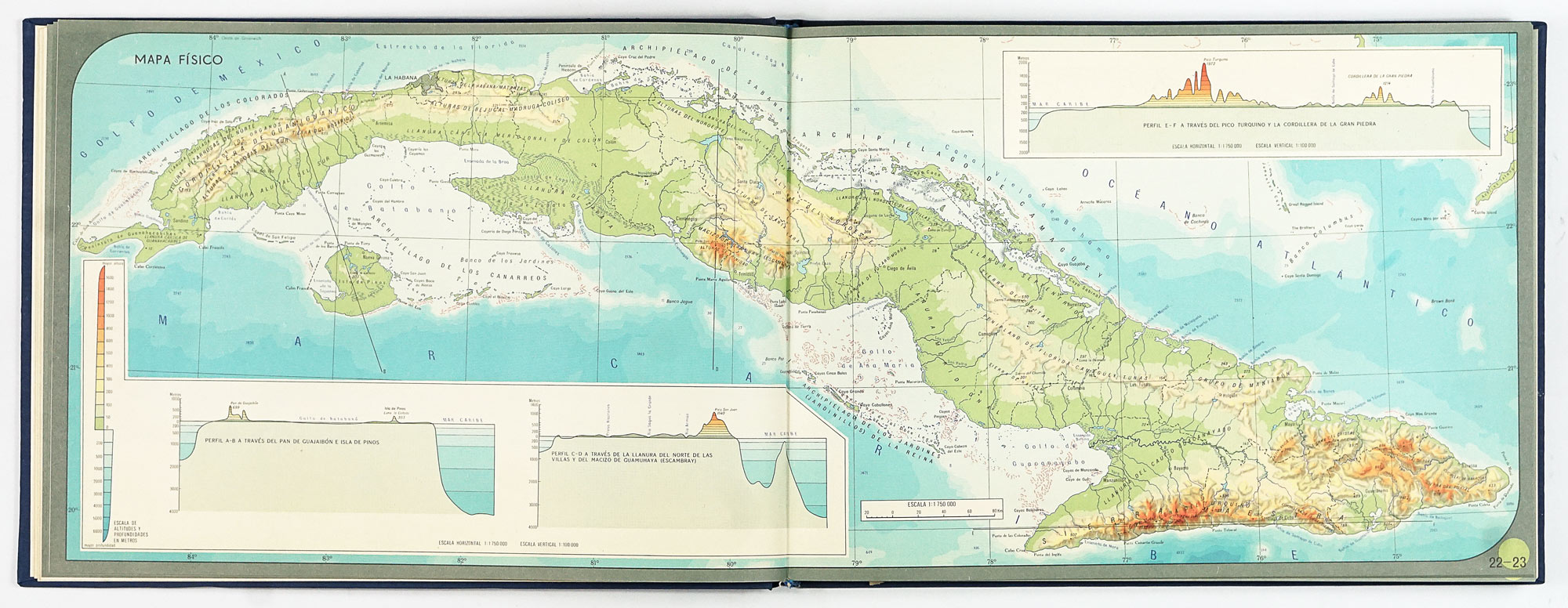

The atlas contains 97 full‑color maps at multiple scales (from 1:1,750,000 to 1:6,000,000), with the General Geographic Map of Cuba executed at an unusually detailed 1:300,000. For maps of Cuban territory, the Lambert conformal conic projection is employed, reflecting a high level of technical sophistication for a national atlas of the period.

Its content is systematically organized into thematic sections, each reflecting both scientific priorities and ideological goals.

1. Introduction

The opening section establishes the symbolic and administrative framework of the revolutionary state. It includes:

- Official national symbols

- A text on the Achievements of the Revolution in Cuba

- Maps of the Political‑Administrative Division (1959 and 1975)

This section sets the tone: geography is presented as inseparable from political legitimacy and state organization.

2. Nature and natural resources

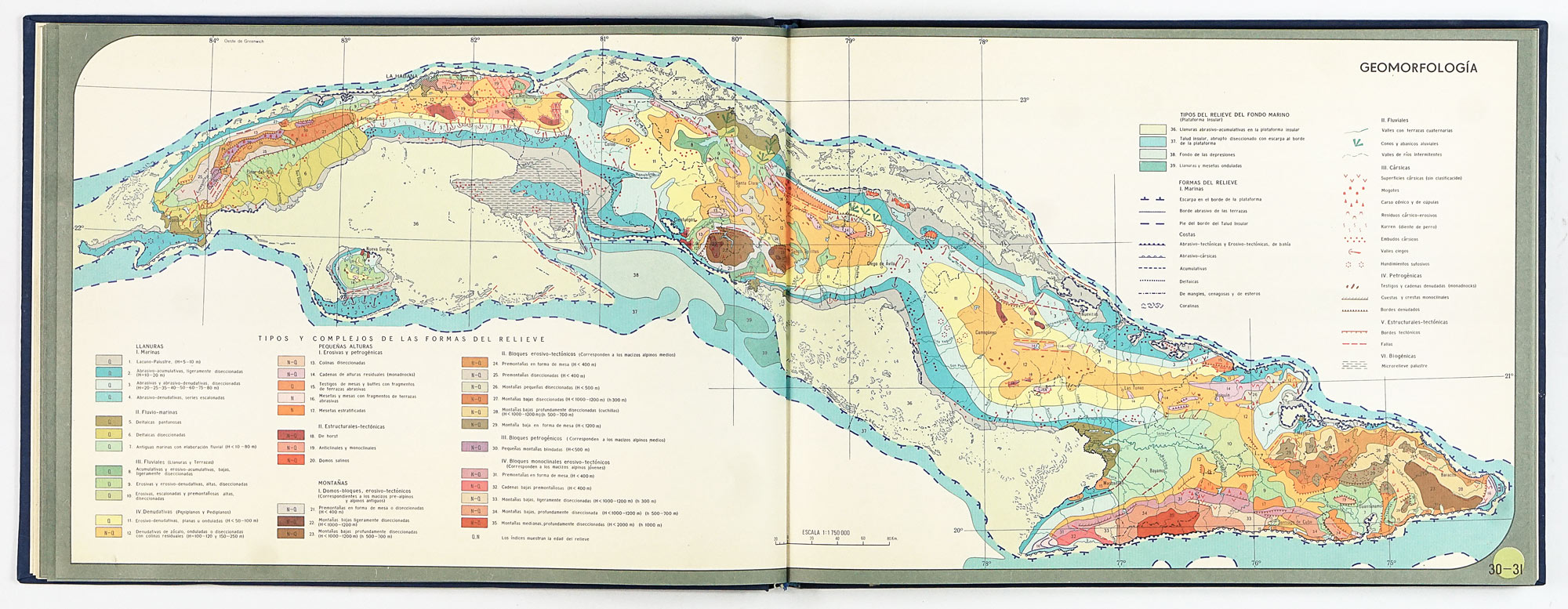

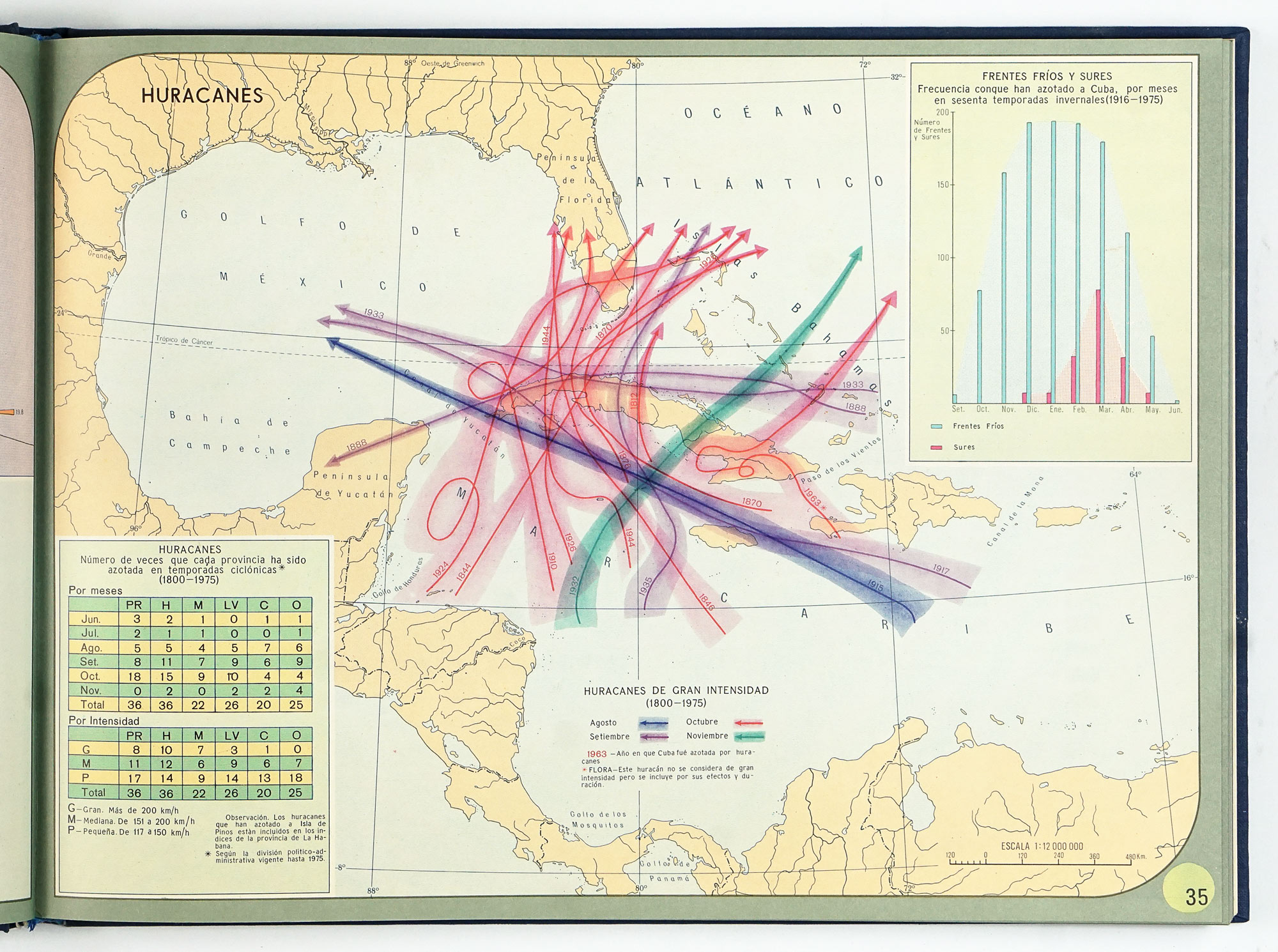

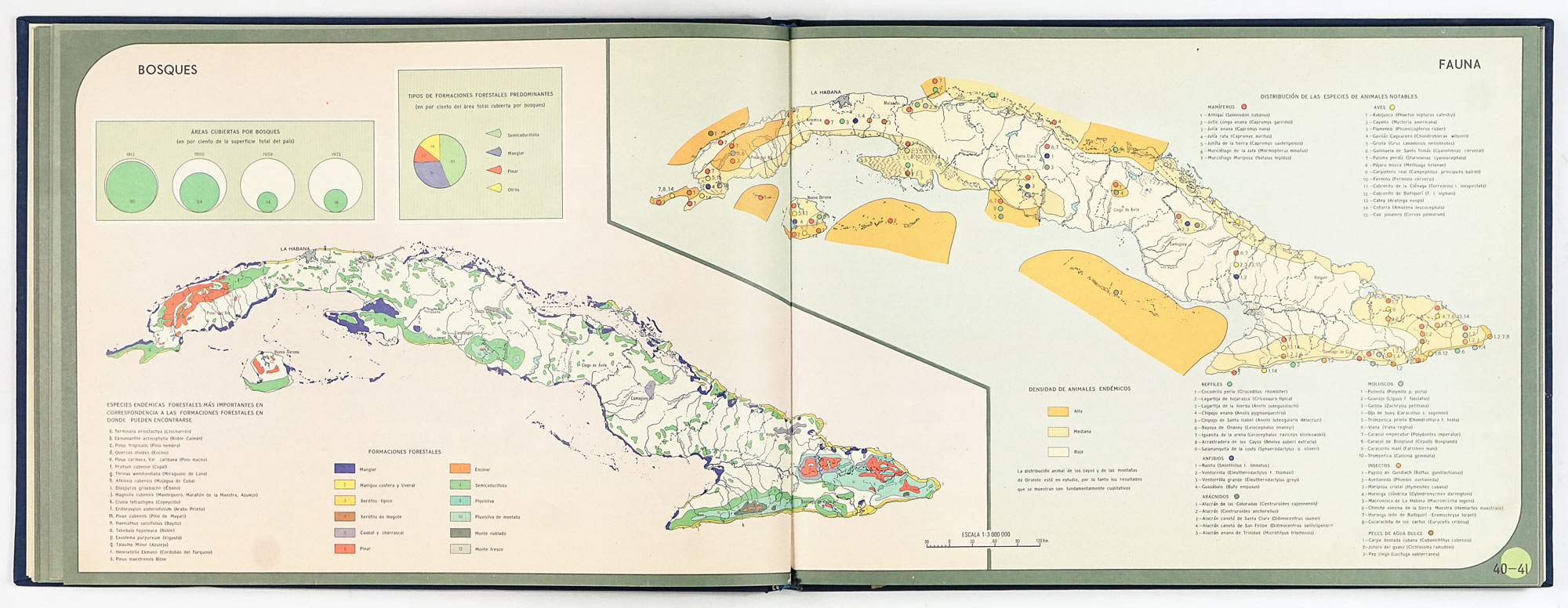

This section demonstrates the maturity of Cuban geographical and environmental research. Maps cover:

- Physical geography, geology, tectonics, and geomorphology

- Climate (temperatures, precipitation, winds, hurricanes)

- Soils, vegetation, forests, and fauna

- Oceanographic maps of surface water temperatures and currents

Of particular note is the map of Protected Natural Landscapes, reportedly the first of its kind in Cuba, signaling an early socialist framing of environmental protection as a collective, state responsibility. The soil maps, based on detailed surveys, underline their importance for planned agricultural development.

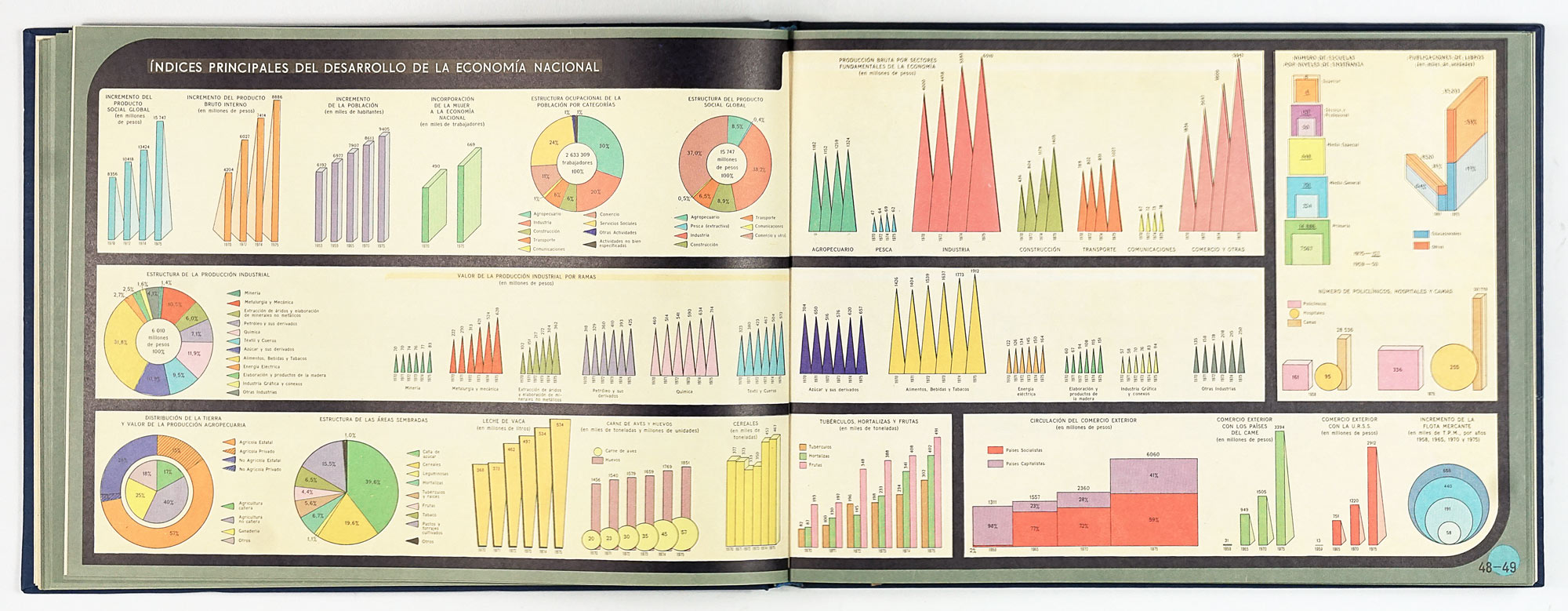

3. Economy

The economic section forms the ideological core of the atlas. It presents a comprehensive cartographic portrait of a centrally planned economy, including:

- A general economic overview

- Energy and electric power

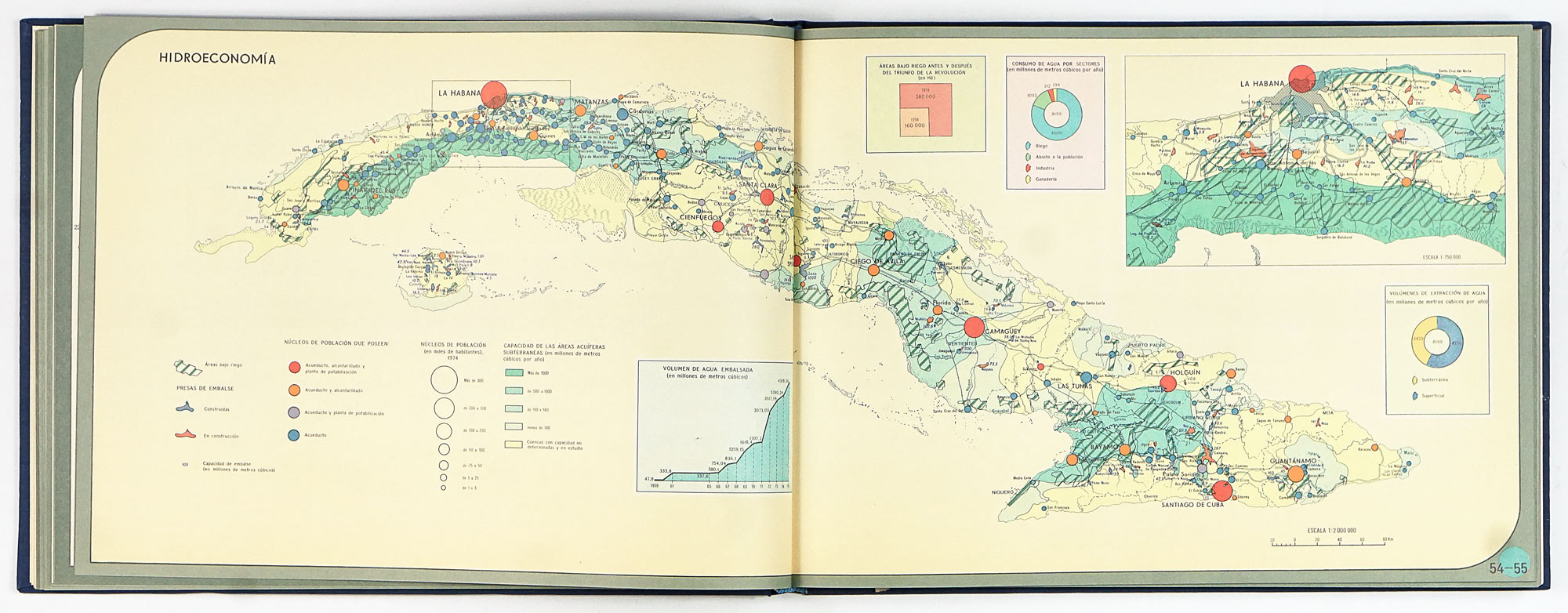

- Hydroeconomics

- Agriculture (land use, sugarcane, mechanization, tobacco, coffee, citrus, fruits, rice, livestock, pastures)

- Industrial sectors (sugar, mining‑metallurgy, chemicals, construction materials, paper and bagasse derivatives, light and food industries)

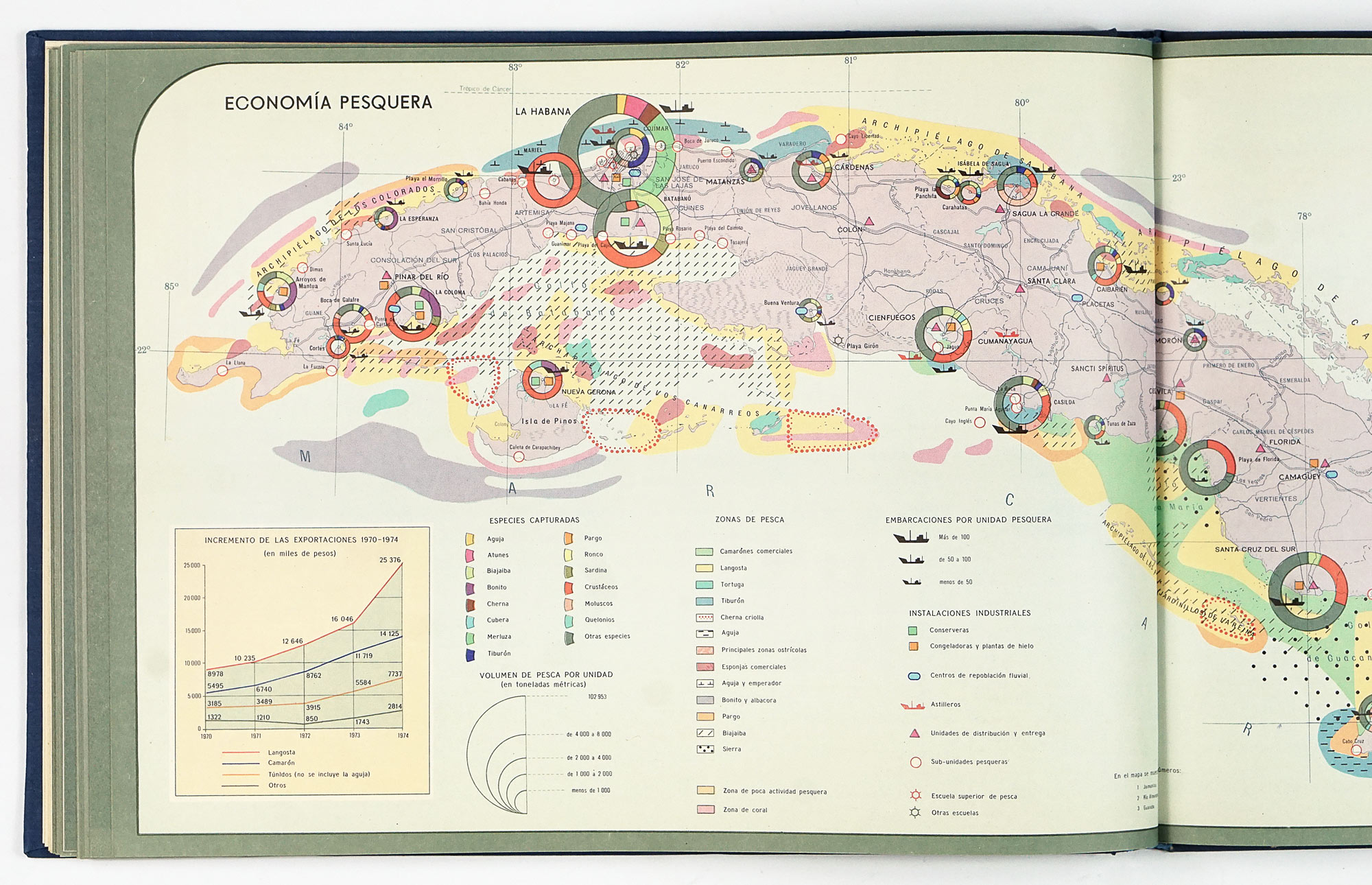

- Fishing, including international waters

- Transport networks and air routes

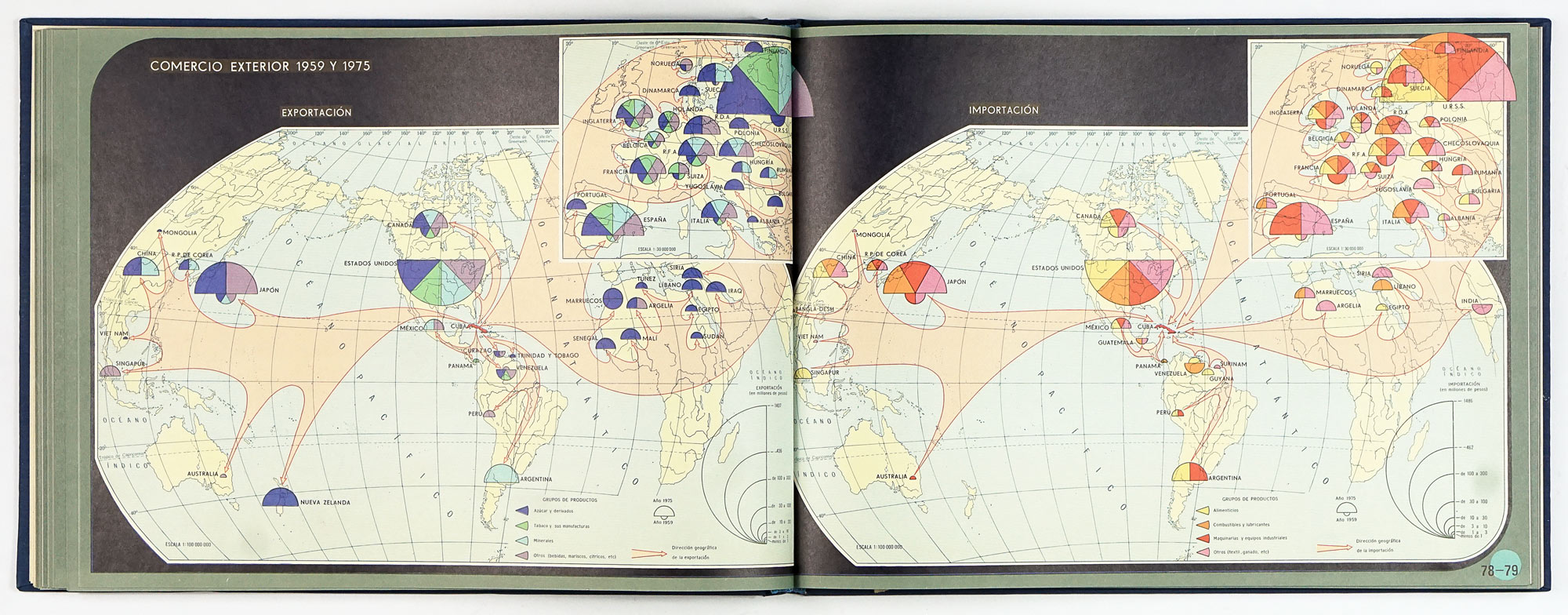

- Foreign trade (exports, imports, and commercial relations in 1959 and 1975)

Sugar production remains central, reflecting its historical and economic importance, while the diversity of additional maps emphasizes industrialization and infrastructural expansion under socialism.

4. Population and culture

This section highlights achievements most frequently emphasized in Cuba’s international self‑presentation:

- Population distribution, dynamics, and economically active population

- Education, including the 1961 Literacy Campaign and mid‑1970s schooling data

- Cultural infrastructure (art schools, libraries, museums, theaters, radio and television)

- Public health and medical institutions

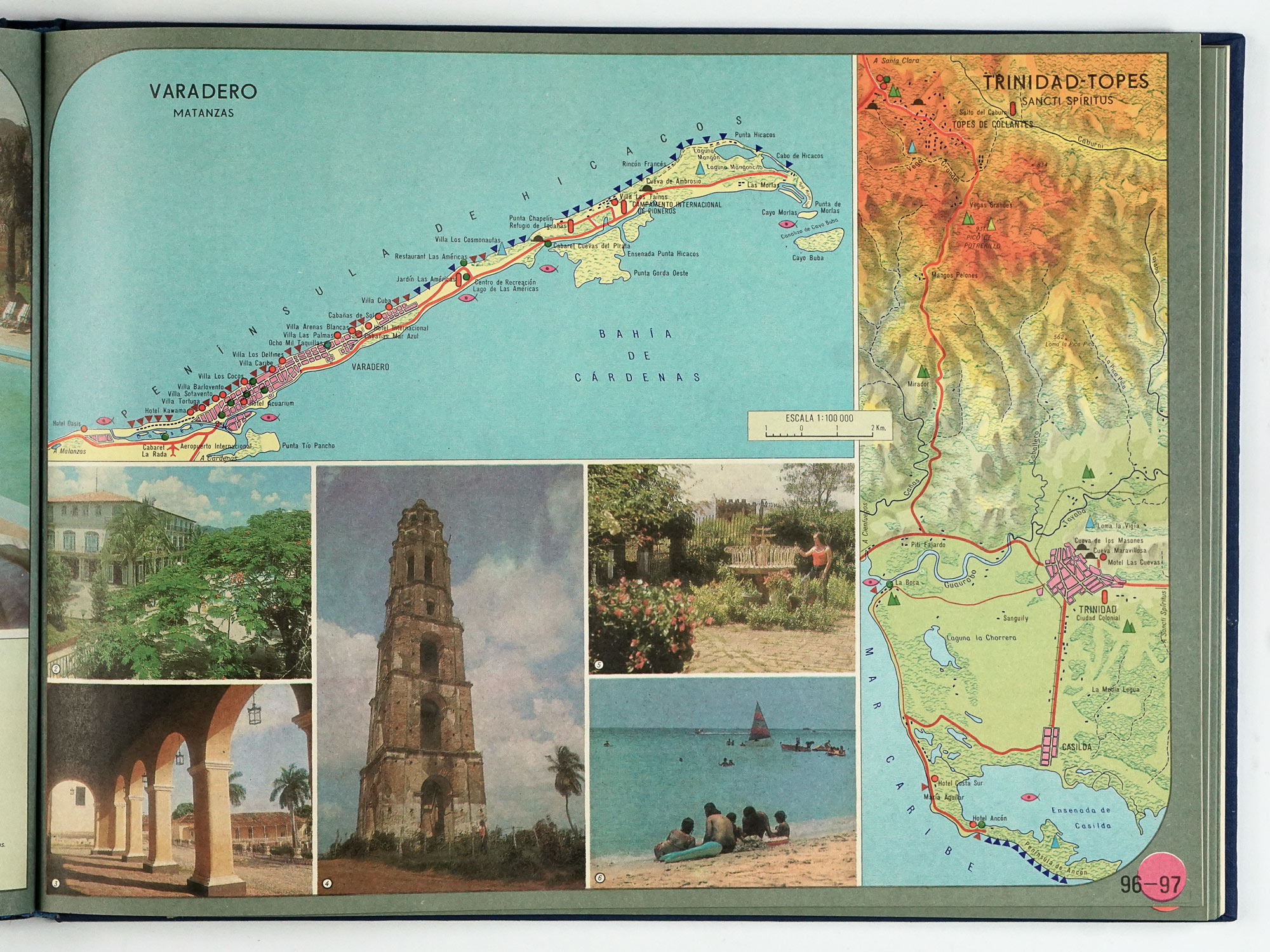

- Physical education, sports, recreation, and tourism

The population maps are particularly significant, as the atlas introduces new cartographic methods in Cuba to show population distribution in relation to economic activity. Tourism is framed not merely as leisure but as an emerging economic sector with strong future potential.

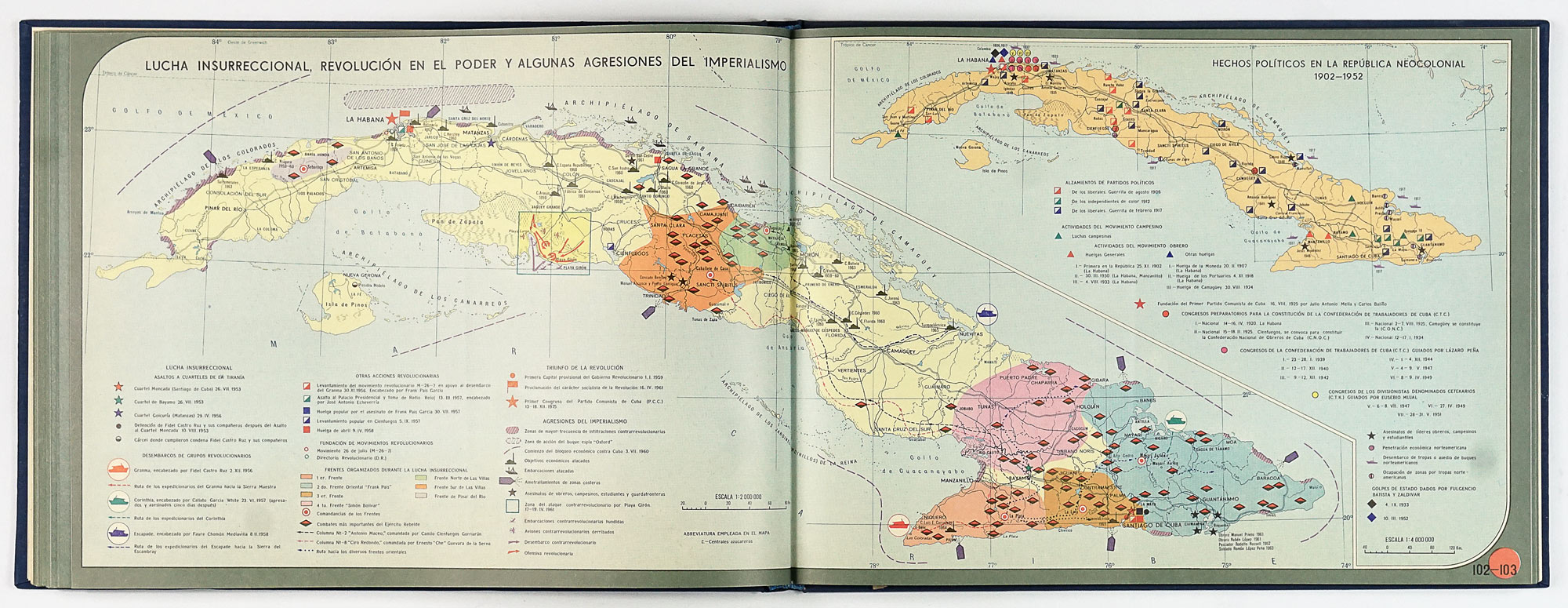

5. History

The historical maps provide a selective and teleological narrative culminating in the Revolution:

- Aboriginal settlement

- Discovery and colonization

- Wars of independence (1868–1902)

- The neocolonial republic (1902–1953)

- Insurrectional struggle, revolutionary victory, and resistance to imperialism

History is presented as a continuous process of struggle whose logical conclusion is the establishment of the socialist state.

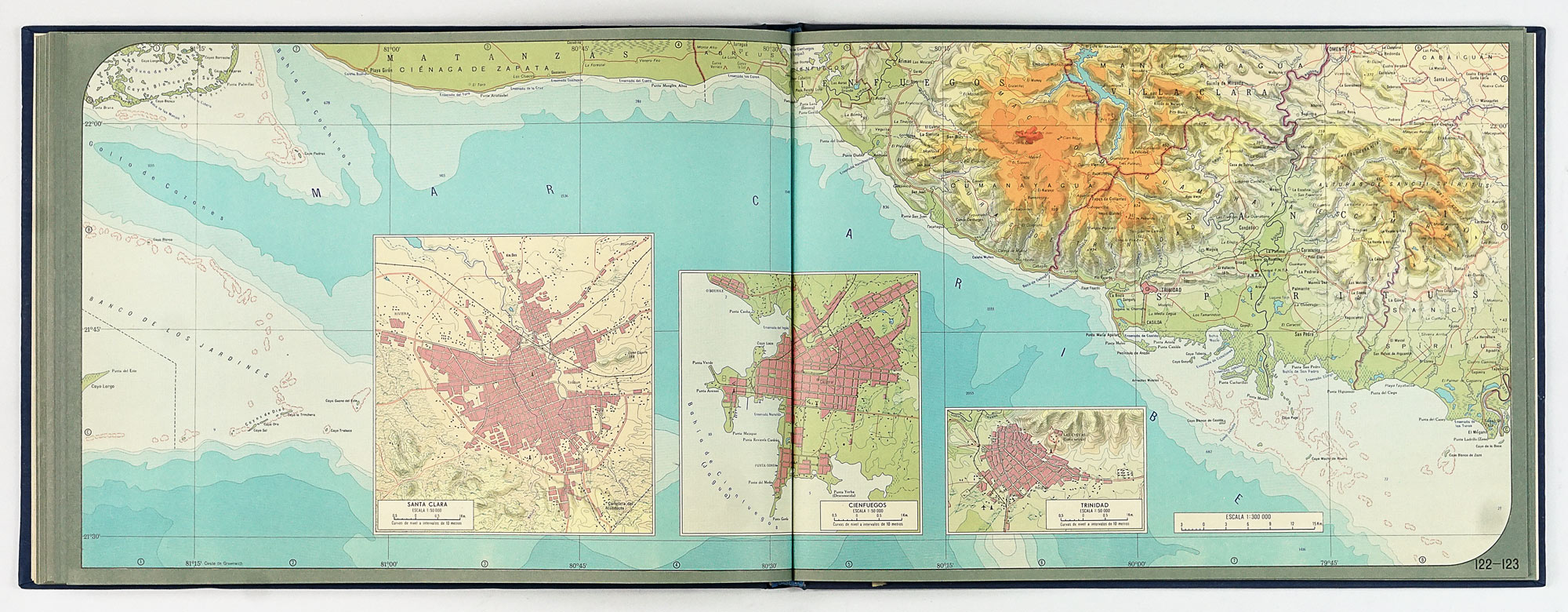

6. General geographic map and city plans

The atlas culminates with the **General Geographic Map of Cuba (executed at a scale of 1:300,000), described as the most complete physical‑geographic map produced in the country to that date. It is accompanied by detailed plans of major cities—such as Havana, Santiago de Cuba, Camagüey, Holguín, and others—selected for their political‑administrative importance, geographic position, or economic potential.

7. Supplementary information

The final section includes complementary statistical data and an extensive Index of Geographical Names, listing more than 9,000 entries arranged alphabetically, reinforcing the atlas’s value as a reference work.

Overall assessment

The ideological framing of this atlas is explicit and inseparable from its purpose, yet this does not diminish its historical or cartographic significance. On the contrary, it enhances its value as a document of how the Cuban socialist state sought to measure, organize, and represent itself at a key moment of consolidation.

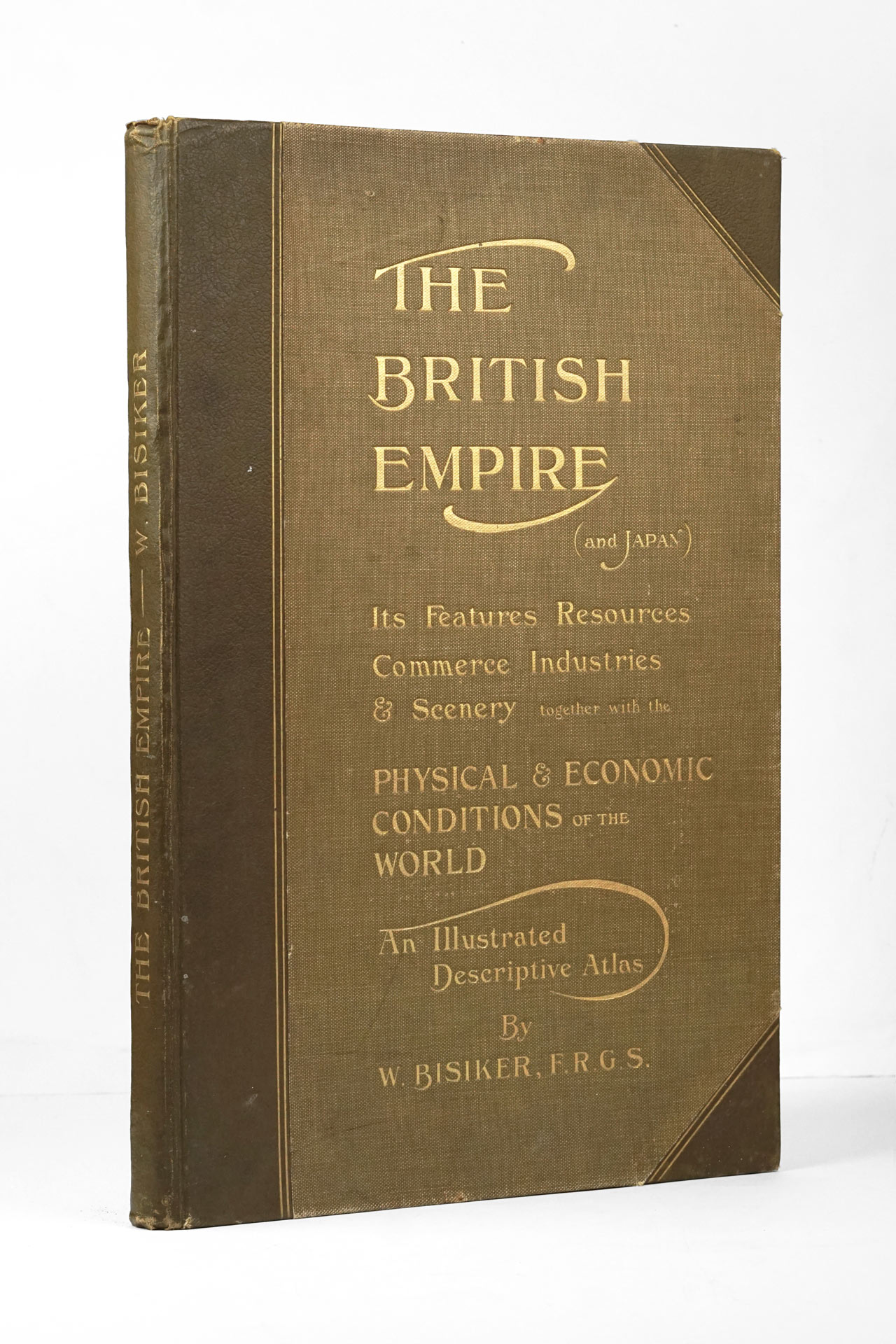

Cartographically, the atlas marks a high point in Cuban national mapping in the second half of 20th century, almost 30 years after publishing of the first national Atlas of Cuba was created by Erwin Raisz and Gerardo Canet.